body snatchers mix, part 6

.jpg)

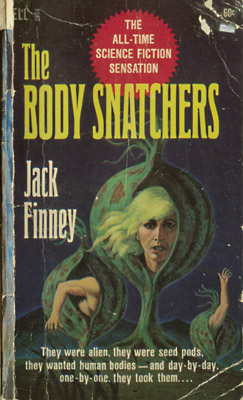

Andy and his painting (Ferrara, 1993)

When you play a piece of music there are so many different ways you could play it. You keep asking yourself what if. You try this and you say but what if and you try that. When you buy a CD you get one answer to the question. You never get the what if.

--Kenzo Yamamoto in The Last Samurai by Helen DeWitt.

I have to wake up in four hours and take a ten-hour flight. Please forgive the lack of description of the tunes.

The tunes are in chronological order, or as near to it as I could get them; if someone knows the recording dates on any of these and wouldn't mind sharing, I'd appreciate it.

These early versions aren't my favorites, though I do like them; my favorites will come later: Ella Fitzgerald, Hank Jones, Keely Smith and Nelson Riddle, Bill Evans, Buddy Tate and Claude Hopkins, Charlie Mingus, Charlie Parker, King Curtis.... Some of those versions want to blow the top of your head off and douse your brain in gasoline.

Wrapup post (or posts? I have over 30 more versions of the song, most of them good, most of them worth sharing) in January.

Big thanks to Reverend Frost and to Girish for making recommendations and helping me track some of these down.

Ray Vega -- Greenhouse

This one is here because greenhouses figured largely in the first two body snatchers films (and a swamp in Ferrara's, sorry) and because I'd already decided on "What Is This Thing Called Love?" for the end when I stumbled onto this track and read that it was based on the same changes. Synchronicity.

[Ray Vega]

Artie Shaw and The Meltones -- What Is This Thing Called Love? (1938/39)

[Artie and the Singers]

Jo Stafford -- What Is This Thing Called Love? (anywhere between 1939 and 1946)

[Too Marvellous For Words]

Anita O'Day -- What Is This Thing Called Love? (1940s)

[And Her Tears Flowed Like Wine ]

Lena Horne -- What Is This Thing Called Love? (1941)

[Stormy Weather: The Legendary Lena (1941-1958) ]

Nat King Cole -- What Is This Thing Called Love? (1943-1944)

[This Side Up ]

Billie Holiday -- What Is This Thing Called Love? (1945)

[Billie Holiday's Greatest Hits (Decca) ]

Django Reinhardt -- What Is This Thing Called Love? (1947)

[The Classic Early Recordings in Chronological Order or, you know, get the box set a la carte @ emusic]

(Spoiler warnings still in effect: plot details, including endings.)

Ferrara's Body Snatchers, in spite of removing the sensational "Invasion of the," does not return to the roots of Finney's story. Of all the versions, it's probably the least like the original serialized story, in spite of having an ending most like it.

The film centers on a teenage girl named Marti Malone, who, like most of the film's characters, has no direct match with any character in the previous stories. Marti is moving to an Army base in the southern U.S., where her father Steve has been sent as an agent of the EPA to monitor use of chemicals on site. Steve's job prompts discussion of chemicals and toxicity, showing a concern for the environment most likely borrowed (like the garbage trucks and those hair-raising alien screams) from Kaufman's film. Yet there are differences with all prior versions of the film, some of them quite striking. Finney's stories were in the first-person; Siegel's mimicked that with the (occasionally cheesy) voiceover. Kaufman's version did not have a voiceover; and Ferrara's version restores it, yet only as a bookending device: two by Marti, at beginning and end, and one at the end by Carol.

Near the beginning of the film, Marti and her family are shown driving across rural highway. When they stop at a gas station somewhere outside the base, looking like approximately the middle of nowhere, Marti goes to the restroom and is rushed by a large man in camouflage. He pushes her up against the door with his hand over her mouth, warning her about people who "get you when you sleep"; Marti manages to slip out the door and away from him, where she screems for her father. Inside the restroom, Steve and a gas station attendant find that there's no one there. It's an odd resolution to the scene, since there seems to be nowhere for the man to have hidden and so it seems to hint that Ferrara is both bending the rules and playing with kid gloves in regards to Marti. This choice, coupled with the choice to have Marti provide voiceover, immediately leads the audience to expect that Marti will most likely survive and therefore reduces the tension in the rest of the film.

Also, by having Marti provide voiceover, Ferrara hints at the possibility of a feminist take on the Body Snatchers story--but it's a version that he is not particularly interested in authoring, though Marti is much more proactive than either Becky or Elisabeth. Marti doesn't share the "wait and see" attitude of the characters in the other films, instead recognizing and dispatching one pod person nearly as soon as she suspected it wasn't human. Siegel's version, on the other hand, is marked by its time, seeming to think that women are mostly for screaming and for being carried. One scene in particular: Miles and Becky in Miles' office, with pod people waiting nearby for them to fall asleep. Miles begins to formulate an escape plan: he'll get the pod people to rush in and then inject them with something to incapacitate them. "It wouldn't work," he says, "I might get one or even two but I couldn't possibly get three of them." And Becky responds: "You're forgetting something, darling--me. It isn't three against one; it's three against two." Every time I see the film, I think that Becky is probably using 1950s-talk for "Goddammit, Miles, breasts don't cause incompetence."

Of all the versions of the story, Ferrara's is most explicitly about the nuclear family. In fact, the shift in focus from a potential couple to an existing family is so striking it causes some critics (like Robert Shelton in "Genre and Closure in the Seven Versions of Invasion of the Body Snatchers" to claim that "There are no children or adolescents at all in the Finney narratives or the Kaufman movie." There are; in Kaufman's version Elisabeth is first shown picking a flower as a group of schoolchildren walk past, being encouraged by their teacher to pick the "pretty flowers"; and later in the same film there is a busload of children unloading and going into a building, a young girl complaining that she isn't tired and doesn't want to go to sleep. Similarly, both versions of Finney's novel contain the prototype for Siegel's Jimmy Grimaldi, the son of the farmers who closed the vegetable stand (presumably to grow pods instead): "A nine-year-old boy came in with his grandmother, with whom he was now living, because he became hysterical at the sight of his mother who, he said, wasn't his mother at all." (Finney '55, p. 22; '78, p. 25)

How did this boy reach this conclusion? What did he see, if anything? Finney and Siegel both leave it to our imaginations; Ferrara shows us: at their new home, after the delivery of several boxes supposedly containing equipment for Steve Malone, Andy walks in on his mother, who is sleeping. As he watches, her body crumples and disintegrates, and the closet door opens. A woman looking just like his mother is standing there, completely nude and impassive. He runs, screaming, and his father catches him to ask what's going on. The pod-Carol descends the stairs and says that the boy had a nightmare. This scene is one of the more terrifying in the film, perfectly capturing what it's like to be a child: dismissed and patronized, worries ignored. Andy's situation is complicated by the fact that in Andy's first day at his new day care, the children were told to paint--their paintings are all strikingly similar; his is different. He's an outsider and knows it, and everyone else does too; and now he knows why.

And here, I think, is where the film falters: Marti is a typical U.S. teenager, at that age where she seems to think most of her family is insufferable, including her six-year-old brother and especially her stepmother. She's somewhat alienated, somewhat self-involved, yet most of her troubles seems rather superficial given the broader context of the story. Andy is a more sympathetic character, old enough to know that something is deeply wrong but too young to do anything about it. He is in danger and knows it; Marti is in danger and doesn't know it; the film has an implied sympathy with Marti's point of view; we know that Marti will most likely live; Marti meets a man she is attracted to, whom her father doesn't like; and Marti has pointless arguments with her family about independence.

The trajectory of the story seems clear early on yet, oddly enough, for me the film serves as a counterexample to Hitchcock's ticking-bomb theory: rather than delighting in suspense I checked off items on a list as they happened. It's probably my coolness towards both the plot and the characters that caused this emotional distance; and I know that some reviewers (including Roger Ebert) found the film very effective. For me the film seemed a strange beast, interesting in how it's different from the others, interesting in what it attempts and where and how it succeeds and fails, but not emotionally engaging. It seems a "faster" watch than the others, the plot developing more quickly and arriving at a sprint sooner (though it slows to a trot in the scene with Marti taking a bath--I'll leave it to the viewers to decide whether that's because Ferrara really enjoyed filming those scenes or because he was both paying homage to Hitchcock and trying to exploit that suppressed knowledge that you're most vulnerable in the bathroom).

In spite of Forest Whitaker's overacting and the general predictability of the story, the film is well-crafted and at least never dull, yet at the end of it all I'm left wondering if at heart the film is really a teenage revenge fantasy in horror-film clothes: after her family is destroyed, Marti and Tim fly away in a helicopter, blowing up the pod peoples' trucks and buildings along the way. In voiceover Marti talks about how revenge, hate, remorse, despair, pity, and fear are all human emotions. This retaliation, coupled with the military setting--military destroying humanity, one civilian and one soldier left striking back at the military--makes me wonder what the film means, or if it even means anything. Are we to make anything of the military setting? Is it merely there for, as Ebert points out, somewhere where pod people would seem to blend in?

And what does it mean when Marti and Tim land in Atlanta and Carol's warning to Steve plays back in slowed voiceover? "Where you gonna go?" Carol says. "Where you gonna run? Where you gonna hide? Nowhere. Because there's no one like you left." Is that to be taken as a haunting memory or an accurate omen? I don't know the answer to these questions.

Ferrara fades to black. In a way it's a spiritual brother to Siegel's ending.

Labels: body snatchers, horror, jazz, movies, vocal

body snatchers mix, part 5

Lightnin' Hopkins -- Feel So Bad

Acoustic country-blues with Hopkins' distinctive reedy voice and some banging piano backup.

[Blues Kingpins]

Waylon Jennings -- Crying

Jennings is not quite up to the melody; his reach isn't as agile as Orbison's, his touch not as deft. He's like a blackhat hacker whose social engineering fails and so he decides to brute force it. It's inelegant but it works.

[Country Giant @ emusic]

Rebekah Del Rio -- Llorando (Crying)

This one's from Mulholland Drive; supposedly it was a one-take recording, which (if true) is all the more amazing considering how well it turned out. This performance is like an angel, watching mute for six thousand years, then deciding it has something to say about sadness.

[Mulholland Drive: Original Motion Picture Score]

Lee Dorsey -- Tears, Tears and More Tears

Lee Dorsey just sounds so damn affable in his songs, like somebody's hip grandfather in sharp shoes and a fedora, incorrigible, bawdy, a metric ton of fun. He's known for working with Allen Toussaint and also the Meters; this one is a Toussaint production with the bass and muted guitars holding down the rhythm and pianos low in the mix accenting it. The horns are in tiptop shape and the vocals give them a run for their money.

[Yes We Can/Night People]

James & Bobby Purify -- You Don't Love Me

Uptempo soul number from James and Bobby Purify, most known for "I'm Your Puppet." This one's a rowdy track with knockout vocals.

[Shake a Tail Feather]

Bo Diddley -- You Don't Love Me (You Don't Care)

Bo Diddley can sing songs that don't contain the words "Bo Diddley," and they're often good, too. Love the harp on this one, especially the echo, and the pounding piano solo is good too. The song has an interesting structure: several verses, a solo, an outro.

[Bo's Blues ]

Oingo Boingo -- Imposter

This song is not afraid. Not afraid of you, or your mama, or your cyborg from the future with the chip in the head. It's from Only a Lad, an album with a gleefully creepy song about a pedophiles, but this isn't that one. This one's about music critics, who are painted less sympathetically than pedophiles. "You take the credit while others do all the work / You like to think you discovered them first / We all know you moved in after it was safe / That way you can never get hurt / You like to play God / You don't believe what you write / You're an imposter" and later, "Your head is firmly lodged way up your butt / Where it belongs."

[Only a Lad ]

(Discussion of Kaufman's film, with spoilers, follows.)

Philip Kaufman, in his remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers, changed the setting from a small town outside San Francisco to San Francisco itself: at the start of the film, pods drift up off the surface of a barren planet, float through space, and descend on earth, the Golden Gate Bridge in the background. There they cover various plants with a gelatinous, translucent substance and begin putting out first roots and then flowers.

Elisabeth Driscoll finds one of the flowers, picks it, gets stared at by a teacher encouraging her young students to pick them, and goes home, where she tells her boyfriend Geoffrey that it might be a completely new species of plant that cross-pollinated from two others, something invasive and dangerous. Unlike in the first film and in the text versions, Elisabeth (the Becky character) is not divorced, but there are signs early on that their relationship is in trouble--the first thing Elisabeth says to Geoffrey is "Too much trouble to pick the mail up off the floor, Geoffrey?" She goes over to him and he pulls her into his lap; they kiss, and Geoffrey interrupts it to shout about the basketball game on the TV behind her.

Matthew Bennell, for his part, is not a doctor but a health inspector working for the Department of Health; he angers the wrong restaurant workers with a promise to have their permit revoked and then spends the rest of the film driving a car with a busted windshield. Elisabeth also works at the Department of Health, and though it's not clear if they've dated before, it is clear that they are attracted to each other. This attraction lends a certain tension to the early scenes in the film, when Elisabeth is still trying to make her relationship with Geoffrey work.

For someone who's seen the original film and noticed the teacher's interest in getting the children to take the flowers home it's probably no surprise that the next morning Geoffrey isn't acting like himself, that Elisabeth is curious and alarmed about it, and that Matthew has a psychologist friend with a number of fairly convincing explanations about why they might be imagining things. In this case the friend is David Kibner, played by Leonard Nimoy. It's an unusual casting choice, especially given the success of the original Star Trek series: Kaufman no doubt expected audiences to be unsurprised at his coolly logical demeanor and perhaps to wonder if it's too obvious that he would be a pod person.

Kaufman also makes a few recontextualizations: not just in changing the setting from suburban to urban but also in making explicit comparisons to disease, evolution, and pollution. All of the topics are covered in dialogue, generally more than once; so the subjects are not subtext but text itself. The change in Matthew's job is interesting, as it shifts him from private practice to civil servant, implying a certain amount of faith in the government yet maintaining the character's interest in contagion and infection. And while Jack is still an author (in this film a poet), he and his wife Nancy also own a mud bath. Nancy is explicitly concerned about environmental damage, at one point commenting that they don't know how the aliens invade humans--"We would never even notice it, not from the impurities we have. I mean we eat junk, we breathe junk--" And Elisabeth's interruption: "Look, I don't know where they're coming from. But I feel as though I've been poisoned today. We've got to take those flowers in and have them analyzed. This is the only thing we know; there is something here."

A number of critics and horror fans have commented that the new urban setting doesn't work (Stephen King, for instance, stating in Danse Macabre that Kaufman lost more than he gained in the change), but I suspect that's a matter of taste. Kaufman is not working on the same scale as Siegel or Finney: Finney's story is a somewhat harrowing but ultimately hopeful story. Siegel aimed for something darker--more loss, more betrayals, a grimmer ending--but had a more hopeful ending (or faux-hopeful ending, depending on your interpretation) forced onto the film. Kaufman states very calmly that there is no reason for hope and will be no survivors.

The aliens in this version sweep up and dispose of their human remains, and throughout the film we see garbage trucks compressing grey fluff in clouds of dust. The first vehicle seen in the film is a garbage truck; and the morning after Elisabeth takes home the flower, Geoffrey is already awake, sweeping something up when the alarm clock goes off. He ignores Elisabeth's questions and takes the trashcan downstairs to a waiting garbage truck. They're everywhere in the film, a constant reminder of both consumption and waste.

The film is also concerned with media, like the Siegel version and the various texts: at Matthew's house on top of a hill, Jack can't pick up any radio stations. Matthew tries several times to call for help, and while some of his later calls are intercepted, most of them go through because the people he's contacting have already been changed. They're careful to appear to help, at least until it no longer matters. When it's clear that the aliens are tired of waiting and are going to force the four of them to be changed, Matthew, Elisabeth, Jack, and Nancy flee Matthew's house, chased by a horde of pod people emitting a hair-raising, thoroughly alien, klaxxon-sounding alarm. The four humans run through dark city streets casting giant shadows, chased on foot and by motorcycle police, tracked by helicopter, and once they're cornered Jack decides to split up from them to find help. Nancy runs after him, leaving Matthew and Elisabeth to go in a different direction.

Eventually they hear some music coming from a ship, giving Matthew the idea to sail away. He goes to investigate, as in the previous film; and what he sees is a ship being loaded with pallets of pods. When he returns, Elisabeth has fallen asleep and won't wake up. He tells her comforting lies as her body disintegrates; and then her replacement sits up and tells him he should quit resisting. This scene is similar to the one near the end of the original film, except that in the original Siegel didn't dare show or imply that Becky was naked (most likely the Hayes code wouldn't allow it). As a result, in Siegel's film we're supposed to believe that the pod person came to life, took the clothes off the remains of the original, put them on itself, and then lay down to pretend to be tired for when Miles returned. No, in this one Elisabeth is naked and she doesn't care: not as she stands up, not as she follows Matthew to the greenhouse nearby, not as she walks through it with dozens of workers milling about, paying her no attention whatsoever. Some people take the nudity as gratuitous, but it strikes me as both logically consistent and purposeful, underscoring the complete alienness of the invaders. It's here in the greenhouse that Matthew makes his final stand, destroying some of the pods and causing a fire before fleeing again to hide.

Throughout the film, Matthew and Elisabeth have been the holdouts in government, trying to maintain their humanity against soul-crushing odds. At the very end we see Matthew at work, appearing dispassionate around the pod people, then in his office cutting out an article, as he did at the beginning of the film. And as the pod people begin to leave the Department of Health, Matthew does too: outside, to the plaza where those strange twisted unforgettable trees are growing, where he hears a voice behind him calling his name. It's Nancy. She steps forward, looking stressed and tearful and relieved to find him, and Matthew raises his arm and emits that klaxxon alarm. In a film explicitly concerned with the environment, starring two civil servants, this ending could be read as both a statement about the effectiveness and integrity of government and as a death knell for hippie idealism: the world is doomed; your government will make sure of it.

Labels: blues, body snatchers, country music, horror, movies, RnB, rock, soundtrack

body snatchers mix, part 4

And the pods march on: next: Kaufman, Ferrara, closing thoughts. You're liking the music at least, I hope.

Howard Tate -- Hold Me Tight

Atypical reggae-inflected soul from Howard Tate.

[Howard Tate's Reaction ]

Otis Rush -- My Love Will Never Die (solo take with piano)

This is a slow, somber take, with Rush apparently still trying to figure out whether the song was meant to be a dirge. The occasional laughter in the background, and Rush's own laughter at the end, suggests that maybe it wasn't.

[Mr. Dixon's Workshop]

Otis Rush -- My Love Will Never Die

Otis Rush tries again, giving the song a lurching rhythm, trilling piano, guitar lines that are sinuous and somehow yearning, and banshee-like vocals leaving no doubt about the pain.

[Essential Collection: The Classic Cobra Recordings 1956-1958]

Magic Sam -- My Love Will Never Die

Magic Sam taking an approach very similar to Otis Rush's, ten years after. Sam and Rush were both on Cobra; West Side Soul is one of the classic blues records. (Interestingly enough, Sam used to play with fellow Chicagoan Syl Johnson in the 50s.)

[West Side Soul]

Dallas String Band -- So Tired

I think it might be easy to take this song ironically, but I love it: the washboard, the fretwork, the melody, the harmony, the progression. And the lyrics, at least what I can make out of them: "So tired of crying / so tired of sighing / so tired of being alone" ... "Though we are drifting far apart / My arms are empty but never my heart / So tired of yearning / For your returning / So tired of waiting for you."

[Texas Black Country Dance Music (1927-1935) @ emusic]

Kay Star -- So Tired

Another one you could take ironically, I guess, but I'm not hip enough to do it. I like the song; I hear something in the vocals that's anachronistic; I can't pinpoint it or explain it, but I like it. It's a very sweet song, uncomplicated and sincere.

[Kay Starr: the Best of The Standard Transcriptions @ emusic]

Junior Wells -- So Tired

Very murky sound on this one, no doubt on purpose--it's like the aural equivalent of squelching your way through thick dark muck that keeps trying to eat your shoes. Wonderful song, though, and the blues were meant to be at least a little discontent.

[1957-1966]

Eddie Bo -- I'm So Tired

Gritty early R&B, Bo rolling out piano riffs and howling about love given in vain.

[I Love to Rock 'N' Roll ]

(Ongoing spoiler warning: texts and films, including endings, discussed below.)

Siegel's 1956 filming of The Body Snatchers hews closely to the established text for most of the film: the story still deals with Miles, Becky, Jack, and Theodora (now called "Teddy"); and Miles' friend the pyschiatrist (now called "Danny" rather than "Mannie"). Miles was divorced more recently than in the book (five months rather than five years) and Becky more recently still (the weekend before the start of the story). As in the book, they had dated each other prior to marrying someone else, and, as in the book, they find themselves falling in love again after the divorces. Early in the film, after scattered reports of people feeling that their family members weren't themselves, Miles jokes that he'd hate to wake up and find that Becky wasn't Becky.

"I'm not the high school kid you used to romance," Becky says, "so how could you tell?"

"You really want to know?" he says. Becky does, so he kisses her.

The film has its differences, though, some of them interesting and others less so, and a few just as inconclusive as the differences among the Finney versions. In Siegel's film, Miles' self-doubts are greatly diminished and the concern over neighborhood upkeep almost entirely eliminated; the only mention of anything decrepit is near the beginning as Miles is driving into town from the train station: he nearly runs over Jimmy Grimaldi, the young son of farmers who have recently closed their vegetable stand.

The film follows Miles, Becky, Jack, and Teddy as they begin to suspect that the people claiming the impossible are in fact correct. Halfway through the film, Miles discovers four pods in his greenhouse, splitting open and beginning to look human. Miles urges Jack and Teddy to leave for help, and Becky tries to phone the FBI as Miles tries and fails to dispatch all the pods in the greenhouse. He lingers, pitchfork in hand, over the one turning into Becky, then decides he can't kill it and instead kills the one turning into him.

Outside town, desperate for somewhere to go for help, Miles drives to his receptionist's house, where he overhears some chilling dialogue:

"Baby asleep yet, Sally?"

"Not yet, but she will be soon, and there'll be no more tears."

Hiding in his office with Becky, Miles delivers the director's message:

"In my practice I've seen people who've allowed their humanity to drain away. Only it happened slowly instead of all at once. They didn't seem to mind."

"Just some people, Miles."

"All of us. A little bit. We harden our hearts, grow callous--only when we have to fight to stay human do we realize how precious it is to us, how dear--as you are to me."

In the morning they see trucks arrive on the plaza and the tarps pulled back, the trucks full of pods. The townspeople collect pods and take them to their cars for distribution. When Jack arrives, their relief is quickly crushed: he's been changed into a pod person; and Danny was one all along. They explain the alien origins of the pods and explain what it's like to be a pod person:

In the morning they see trucks arrive on the plaza and the tarps pulled back, the trucks full of pods. The townspeople collect pods and take them to their cars for distribution. When Jack arrives, their relief is quickly crushed: he's been changed into a pod person; and Danny was one all along. They explain the alien origins of the pods and explain what it's like to be a pod person:Miles: "I love Becky. Tomorrow will I fell the same?"

Danny shakes his head. "There's no need for love."

"No emotion? Then you have no feelings? Only the instinct to survive. You can't love or be loved, am I right?"

"You say it as if it were terrible; believe me, it isn't. You've been in love before; it didn't last. It never does. Love. Desire. Ambition. Faith. Without them life's so simple, believe me."

And as if one betrayal were not enough, there's the climax of the film: Miles and Becky, exhausted, on the run from the entire town, just like in the book. Except they hide in a tunnel under some slats, rather than under some brush in the fields, and Miles leaves Becky to investigate some beautiful music which Becky says must mean that someone still knows what love is. When he returns he finds Becky in a different location; she's too tired to walk so Miles picks her up and begins to walk out of the tunnel. He trips and they fall into a mud puddle, where they kiss, and Siegel springs a surprise on a 1950s audience familiar with the source material: Becky looks up at Miles exceptionally coolly; Miles pulls away, face registering alarm and disgust. She's been changed. She tells him it's not painful, and he should quit resisting; then as he flees she shouts at the others that he's there.

They let him go to the highway, where he is taken for a drunk or a maniac; he finds the back of a semi loaded with pods and then, on the street, continues to shout his warnings into the camera: "They're coming! You're next!"

And there it would have ended, except that the film tested poorly and the studio forced a change. So Siegel shot a pair of tacky bookends: starting the film with a psychiatrist arriving at a hospital to find Miles panicked and unconvincing; and ending the film with the psychiatrist leaving the room and encountering a truck driver being pushed in on a gurney, with a broken arm and two broken legs. The psychiatrist is informed that the man ran a red light and crashed into a bus, tipping his truck over and spilling a cargo of large and unusual things that look like seed pods. So he goes to the phone, where he shouts at the operator to get him the FBI right away, and yes it's an emergency. And there the film ends.

It's a strange ending for a number of reasons. Generally it's accepted as an inferior ending to the one Siegel intended, which was to leave Miles looking like a stark raving lunatic on the freeway. The new ending might be considered a challenge to the auteur theory in that the studio forced Siegel to add it, against Siegel's wishes. Yet it's also somewhat appropriate in that the new ending hews more closely to the ending to the serial originally optioned: invoking the federal government to come solve local problems with national implications. And yet it's also a sly ending, a subtly suversive ending, on Siegel's part: the pyschiatrist believes Miles and calls for help. "Excellent," we think. "The day is saved." Except we see "The End" before we hear what happens next, and so it's easy to forget that Miles also tried to call for help, and that he could not get through because the pod people already controlled the phone system.

Besides, I'm not sure how many people the new ending relly convinced: I saw the film as a child and didn't see it for a decade afterwards; what I remembered of it was not the call to the FBI but Danny's betrayal and the unveiling of the truck loaded with pods.

In some ways Siegel's The Invasion of the Body Snatchers reminds me of Howard Hawk's The Thing: both deal with an alien invasion of murderous perambulatory plant matter; but The Thing has no patience for the federal government or the visitor, and The Invasion of the Body Snatchers takes a more patient, cautious, watchful stance. There's probably fertile soil there for someone willing to argue that the two films are the Rio Bravo and High Noon of science fiction.

It's common to put Finney's novel and Siegel's film into a Cold War context, and Glen M. Johnson does it as well as anyone. A bit from "'We'd Fight .... We Had to': The Body Snatchers as Novel and Film":

Finney complicates the simplistic them-vs-us forumula by making his invaders invisible--a force or consciousness that conquers by taking over the minds and personalities of ordinary people. So the "body" snatchers become apt symbols for ideological subversion, fear of which was a characterisitc form of anxiety in the American fifties.Johnson, like many authors discussing the story's Cold War origins, mentions brainwashing: "it is suggestive that The Body Snatchers is set in August 1953, immediately after the Korean armistice, when American newspapers were full of incredulous reports about the 'turncoats' who chose Communism over a return home."

At the time of the stories' publication, HUAC's investigation into Communist propaganda in Hollywood, followed by its blacklist of the Hollywood Ten in 1947, was not yet ten years past. Joe McCarthy had spent several years in Congress making rabid declamations against suspected communists as chair of the Subcommittee on Investigations, and only in late 1954, after several years of bellicose and frequently baseless accusations, had he netted a formal censure in the Senate. It's easy to imagine that the alien invasion in the body snatchers stories serves as a metaphor for Cold War anxieties--either as a fear of communism or as a fear of McCarthyism. If there's one thing central to U.S. belief it's rugged individualism, and both sides were no doubt feeling an overwhelming pressure to conform. So it's somewhat common that the series of betrayals in the story, executed by family and friends, reminds people (ironically or not) of J. Edgar Hoover's sensationalist warning in Masters of Deceit that "there are thousands of people in this country now working in secret to make it happen here." Furthermore, it's easy to view the sleep metaphor as freighted with political baggage, especially given the "sleep no more" propaganda common during the Cold War.

Yet as J. Hoberman notes in "Paranoia and the Pods,"

Sorting out the politics of the men who filmed Invasion of the Body Snatchers is not easy. Siegel has described himself as a liberal, although his ouevre is more suggestive of a libertarian belief in rugged individualism. Wanger, a producer with an interest in topically political material, was responsible for both the crypto-fascist Gabriel over the White House (1933) and the prematurely anti-fascist Blockade (1938) as well as for such New Dealish genre exercises as You Only Live Once, Stagecoach, and Foreign Correspondent.Hoberman goes on to note that Mainwaring, the film's screenwriter, had written the "relentlessly perfunctory" anti-communist film A Bullet for Joey and that Invasion of the Body Snatchers' script was rewritten by Richard Collins, "a former Communist Party functionary, co-author of the once notorious Song of Russia (1943), [and] an announced unfriendly witness first subpoenaed by the House Un-American Activities Committee in autumn 1947 among the original Hollywood Nineteen" who later turned witness for the FBI. So the film might be read as an anti-Communist fable, or as a satire of McCarthyism, or simply as a richly metaphorical work authored by a number of men with strikingly different philosophies.

Siegel, for his part, seems content to think of the film as about conformity in general: "It's the same as people who wlecome going into the army or prison. There's regimentation, a lack of having to make up your own mind, face decisions.... People are becoming vegetables. I don't know what the answer is, except an awareness of it. That's what makes a picture like Invasion of the Body Snatchers so important." (Parkes, "There Will Be No Survivors")

And Finney denies all of these interpretations, both here and elsewhere:

For years now, I've been amused by the fairly widely held notion that The Body Snatchers has anything to do with the cold war, McCarthyism, conformity... It does not. I was simply intrigued by the notion of a lot of people insisting that their friends and relatives were impostors.

--"Paranoia and the Pods," Sight and Sound May 1994, p.31

I have read explanations of the "meaning" of this story, which amuse me, because there is no meaning at all; it was just a story meant to entertain, and with no more meaning than that. The first movie version of the book followed the book with great faithfulness, except for the foolish ending; and I've always been amused by the contentions of people connected with the picture that they had a message of some sort in mind. If so, it's a lot more than I ever did, and since they followed my story very closely, it's hard to see how this message crept in. And when the message has been defined, it has always seemed a little simple-minded to me. The idea of writing a whole book in order to say that it's not really a good thing for us all to be alike, and that individuality is a good thing, makes me laugh.So the question is, then, whether the author is the final word on what a text means. I think the author often has a good idea of what he intended, except that even he might not realize all of the intentions and subtleties: I'm reminded of Ray Bradbury's comment in the afterword for Fahrenheit 451 that for decades he didn't notice that Faber was the name of a pencil company and that Montag was the name of a paper company.

--personal letter to Stephen King, December 24, 1979, as cited in Danse Macabre, 1983 Berkeley paperback, p. 306-307

And, too, it's obvious that the reader (or viewer) must understand, process, and interpret the parts of a story for it to have any meaning. Those interpretations are necessarily personal affairs, at times idiosyncratic or conflicted but always dependent on associations with existing knowledge. Is the story about communism? McCarthyism? The Red Scare? The case for each of those could be made, sure, and frequently is. Art is largely an interpretive matter and almost never yields as unequivocal results as math. And should it?

Labels: blues, body snatchers, country blues, horror, movies, RnB, vocal

body snatchers mix, part 3

Some more songs tangentially related to the Body Snatchers stories, and more about the stories (with spoilers) below that:

Jimmy Bo Horne -- Get Happy

There's something here that reminds me of much of George McCrae's work, probably in the simple composition and the repetition, but also in the reliance on a sweet hook and an energetic horn section in a poppy R&B track with high-flying vocals. Another happy song, appropriately enough.

[The Legendary Henry Stone Presents: Jimmy Bo Horne @ emusic or @ amazon]

Shirley Bassey -- Hey Big Spender (Wild Oscar mix)

Bassey likes to make these big brassy music numbers that go well with Bond films (Goldfinger, Moonraker, Diamonds are Forever) and that get a deft parody in The Life of Brian ("He had arms ... and legs ... and hands ... and feet / This boy whose name was Brian"). The remix here decides that brassy isn't brassy enough, and so kicks it up a notch: adding breakneck percussion, muted guitar, vocal effects, and tempo changes.

[Shirley Bassey - The Greatest Hits]

J.J. Cale -- Call the Doctor

Countrified blues-rock, subdued delivery, plodding bass, sour horns, and electric guitar swelling into a stoned melancholy solo. The description sounds horrible but Cale pulls it off somehow.

[Naturally]

Eddie Floyd -- Bring It on Home To Me

Easy-going R&B, not pining, not pleading, not arguing a case so much as pointing out what a good time you could be having--hoping you'll come to your senses and come join in.

[Eddie Floyd - Chronicle: Greatest Hits]

Lou Rawls -- Bring It on Home

Nevermind the showboating at the beginning; give the song a minute (actually, 45 seconds). Let the bass come in and the funk get dropped; let Lou gather his evidence and practice his line of argument. It's a smooth-talking dapper performance, pitch-perfect and with just enough edge on it to let you know he's serious, but not so serious as to keep the jurors from clapping.

[Anthology]

Jack Finney has published at least three different versions of Body Snatchers: first as serialized in Collier's in November and December 1954, then as a book in 1955 (expanded and given a different climax) and then with further edits in 1978 to coincide with Philip Kaufman's second film version of the story.

The three have strong similarities, as could be expected. The text versions take place in Santa Mira, a small town outside San Francisco, and feature a doctor named Miles Bennell, a former flame named Becky Driscoll, a psychologist friend named Mannie Kaufman, a writer friend named Jack Belicec, and his wife Theodora. At the start of the story, Becky approaches Miles and tells him of her cousin Wilma who's become convinced that her Uncle Ira is not actually Uncle Ira; when they visit Wilma, she explains that her aunt hasn't noticed because she is also not her aunt. From there the details accrue suggesting that the humans are being besieged by aliens intent on replacing them, and the small group of humans decide to fight.

Along the way Becky and Miles, both divorced, find themselves increasingly attracted to each other. Becky has divorced recently and Miles five years earlier, yet Miles continues to be bothered by his divorce, taking it as a sign of some shameful defeat. There are scattered mentions throughout the novel, most of them wry, and others which seem either self-deluding or callous and sexist:

I'd seen Becky at least every other night all the past week, but not because there was any romance building up between us. It was just better than hanging around the pool hall, playing solitaire, or collecting stamps. She was a pleasant, comfortable way of spending some evenings, nothing more, and that suited me fine.Then there's this more telling passage as Miles is shaving:

--Body Snatchers, '55, p. 24

'You handsome bastard,' I said to my face. 'You can marry them, all right; you just can't stay married, that's your trouble. You are weak. Emotionally unstable. Basically insecure. A latent thumb-sucker. A cesspool of immaturity, unfit for adult responsibility." ... I cut it out, and finished shaving with the uncomfortable feeling that for all I knew it wasn't funny but true, that having failed with one woman, I was getting too involved with another, and that for my sake and hers, she should be anywhere but here under my roof.Both the paperback versions share Miles' self-doubt following his divorce, his penchant for prescribing sedatives, his passive wait-and-see attitude in the face of an obviously mounting crisis, and the curious marker of the body-snatched: an indifference to neighborhood upkeep. A visiting salesman complains that it's hard to get into and out of the town; coffee is hard to come by and tastes bad when a restaurant has it; and Miles notes that his Coca-Cola is warm. And outside the restaurant, on a littered street:

--Body Snatchers, '55, p.76

"Miles," she said in a cautious, lowered tone, "am I imagining it, or does this street look--dead?"Of the three versions, the Collier's version is probably the hardest to find: so far as I know it was never collected and published separately without changes, and it doesn't seem to be available in various academic databases, so finding it most likely requires access to the original magazines. I haven't read this version but I have the other two, and they're fairly similar. One of the more striking differences between the two novels happens early on when Miles mentions his car: "I drive a '52 Ford convertible, one of those fancy green ones, because I don't know of any law absolutely requiring a doctor to drive a small black coupé." (Finney '55, p. 13)

I shook my head. "No. In seven blocks we haven't passed a single house with as much as the trim being repainted; not a roof, porch, or even a cracked window being repaired; not a tree, shrub, or a blade of grass being planted, or even trimmed. Nothing's happening, Becky, nobody's doing anything. And they haven't for days, maybe weeks."

--Body Snatchers '55, p. 108

So early on Miles seems like a big spender, maybe a bit arrogant, maybe living a lavish lifestyle, with no time for Becky. In the 1978 version the passage is changed: "I drive a 1973 Mercedes two-seater, a nice fire-engine red job, bought used, to maintain the popular illusion that all doctors are rich." (Finney '78, p. 13)

Yet most of the differences between the two versions are subtle, perhaps inconsequential--instead of golf and swimming, Miles plays tennis, things like that. (In fact, the two versions seem so similar that the cynic in me suggests that the 1978 revisions were published simply to allow an extension on the copyright--copyright terms at the time were much more limited and the one on Body Snatchers had nearly run out.)

In the two novel versions Miles, Becky, Jack, and Theodora are increasingly persecuted, then flee town only to find that they don't know where to go or what to do. So they return to town, where they are split up. Becky and Miles hide in a field just outside town--the field where, it turns out, a professor had discovered what he thought was most likely an alien plant, and then a few days later retracted his story. It is here where the aliens are growing their pods for distribution, and Miles and Becky make a desperate last stand, setting fire to the fields and smashing pods. The aliens recognize their defeat and the pods detach from the plants, fly up off the ground, and leave the planet. Miles and Becky reunite with Jack and Theodora and discover that the aliens have a curiously short lifespan; most of them die off within a few years.

The serial version is apparently much different: Robert Shelton in "Genre and Closure in the Seven Versions of Invasion of the Body Snatchers" mentions that the 1955 Dell paperback "is based on, and twice the length of, the serial" and that "in the 1954 serial, a posse of FBI agents armed with 'riot guns' and 'small, light, almost dainty-looking machine guns'" arrives on site, attracted by Miles' fire, and helps fend off the alien invasion.

What does it mean that the endings are so different? What point was Finney trying to make, or deciding not to make? Catherine Jurca, in "Of Satire and Sofas," calls the novel "an allegory of postwar suburbanisation," yet the article is too brief to offer much supporting evidence and it's left to the reader to remember the United States' postwar population boom and the move from the cities to the suburbs.

Michael Parkes, in "There Will Be No Survivors," takes the novel as a metaphor for a different kind of encroaching conformity, and the pods as representing a different threat to identity: the introduction of television into American culture. Parkes notes that "between 1948 and 1955, television was installed in nearly two-thirds of the nation's homes and became the mythic and ideological unifier of the fragmented post-war family" and served "as a sign of suburban achievement," yet one that moved the family away from the hearth and conversation to the television and silent viewing. Parkes notes the effect of television on bars and cafes, as well, and its corollary to the cafe scene in the novel when Miles and Becky go to the Sky Terrace in the Siegel film to find few customers and no live music, but instead a jukebox: "the artistry and individuality of the original band has been 'snatched' and replaced by an inferior technological substitute." In this reading, Parkes considers the story's message somewhat ironic, calling it "an anti-media discourse which in itself is contradictory, as the film [and book] itself exists within the media."

This interpretation of the book as an anti-media, Luddite response to technological innovation is interesting; yet by far the most common reading of the story is as a metaphor for the political climate in the United States during the Cold War--whether as one about McCarthyism or as one about the Red Scare. More on that, and on Finney's and Siegel's reactions to it, next post.

Labels: about fiction, body snatchers, country blues, horror, RnB, vocal

Roots Canal: The Bug's Got a Big Bazoo!

Gene Phillips -- Big Bug BoogieTuwa sent me a link the other day to a wonderful album on eMusic full of songs I'd never heard before, mostly by artists I'd never heard of. Not only is the music exceptional, but the story behind it is pretty good, too. It was put together by a Toronto blues collector and DJ named Eddy B, from records in his private collection that were so rare they weren't even listed in the standard blues discographies. The first in the series was hard-core blues from the '50s and '60s, but Volume Two goes back to the late '40s and early '50s when jazz was metamorphosing into jump blues into R&B and finally into rock'n'roll (see How Rock Really Began). According to Eddy B's website, Volume Three is coming out next year featuring "Midnite Mammas" from the '40s to the '60s. Can't wait.

This song, by one of the few artists on the record whose work I already knew, has some of the funniest R&B lyrics ever put on wax:

Hey bartender, there's a big bug in my beerGene Phillips played Texas-style blues guitar in LA's pioneering R&B scene and recorded regularly with many of the great artists whose songs I've already posted like Wynonie Harris, Jack McVea, Wild Bill Moore, Duke Henderson and Rabon Tarrant. He must have been quite a character. What else can you say about a guy whose CD collections are named Drinkin' and Stinkin' and I Like 'em Fat?

Hey bartender, there's a big bug in my beer

One eye is red, the other is green

The craziest old bug that I've ever seen

Hey bartender, there's a big bug in my beer

Whoo bartender, the bug's got a big bazoo

Whoo-ee bartender, the bug's got a big bazoo

Big old head from there to here

Big old mouth drinking all my beer

Hey bartender, the bug's got a big bazoo

One more beer, without the bug

One more beer, without the bug

One more beer, without the bug

One more beer, without the bug

Well there's bugs on the ceiling, bugs on the floor

All kinds of bugs creeping through the door

There's bugs on the table, bugs on the beer

I do believe there's bugs in my hair

Hey bartender, the bug's made himself a home

Hey bartender, the bug's made himself a home

Every time I take a sip

The big old bug tries to bite my lip

Hey bartender, he's drinking up all the foam

Hey bartender, one thing I've got to know

Hey bartender, there's one thing I've gotta know

If the beer is his, then he can stay

But if it's mine, all I can say

Hey bartender, the big bug's gotta go!

Bonus Track: As I was listening to some of the tracks from this CD, I was startled to hear another "voot" song. About two minutes into the song, you'll clearly hear them sing, "Voo-it! Voo-it! Voo-it!" I guess I'll have to add this to my definitive Voot Detective post.

Billy Langford with His Combo -- Be-Bop on the Boogie

[Midnite Blues Party, Volume Two (eMusic)]

body snatchers mix, part 2

I guess I should have explained a bit more about the mix last time: most of the songs are tangentially related to the Body Snatchers stories at best, and the mix isn't limited to what could fit on a CD (mostly because I'm not one to make tough decisions). Along the way we'll see some songs with a passing resemblance and others that are different from how we remembered them.

Betty Everett and Jerry Butler -- Love Is Strange

I've written about Betty Everett twice before. This one is one of the better tracks off Together--sweet lyrics and a sweet duo, but what sells it for me is when each of them take it solo towards the end. And then I'm completely sold, yes.

(As for the rest of the LP ... no. It's mostly middling, with tracks that tend to stop at competent without making it to genuinely affecting, and I'm not surprised it's gone out of print. I can't speak for the CD linked below, though--haven't heard it and it's awfully pricey for me to pick up.)

[They're Delicious Together]

Little Milton -- If You Love Me

If guitars were animals, PETA would stage a protest about this song.

[Anthology 1953-1961 ]

Little Johnny Taylor -- If You Love Me (Like You Say)

Keeping with the Chicago blues, the horns, the electric guitars, and the general theme--this one has a smoother melody on the vocals, less grit on the delivery, more syncopation on the horns, and an organ buried in the mix.

[Greatest Hits]

Muddy Waters -- I Feel So Good

Blues piano with a harmonica and a drumset rocking the joint, letting the public know that feeling good can be contagious.

[At Newport]

Ann Peebles -- Slipped, Tripped, and Fell in Love

Three great things about this song: the bass, the organ, the background vocals. The first one runs throughout; the next two stop in for tea and leave right after. You'd consider it rude, except now you're friends and you just hope they can stay longer next time.

[The Best of Ann Peebles: The Hi Records Years]

Dreaming permits each and every one of us to be quietly and safely insane every night of our lives.

--William Dement of the Stanford University Sleep Research Centre, Newsweek, November 30 1959

A bare-bones plot description of the Body Snatchers stories (all of them): residents of a community come to suspect that certain loved ones are not themselves, but are perfect physical replicas without any genuine emotional responses. They discover that people are in fact being destroyed and replaced by impostors hatched from alien pods, one by one, as each one of them sleeps. A small group of people decide to fight the aliens, and at least two of them are in love.

From there the details differ--in the characters, locations, resolution, and treatment of themes, with implications about each story's beliefs. But fundamentally the story is about love and vulnerability and the loss of individuality. It's about being human and getting tired and needing to sleep. We're no more vulnerable than when we sleep, as Wes Craven knows, but Finney didn't create a sardonic villain to dispense gory deaths; instead he poses the more psychological question: who will we be when we wake up?

It seems a silly question, easy to laugh off, yet sleeping itself is somewhat troublesome. "We all go a little mad sometimes," sure. We might go a bit unhinged on hearing some devastating news, but that's not all, is it? It's a truism that no one wants to hear about anyone else's dreams, and probably even psychiatrists are faking it, but what are these things? Our brain tells us the earth is a swamp and that people drive Yugos over fallen mossy trees past dully interested brontosauri, and then we get up in the morning and yawn and stretch and go make tea or cofee. Our brain sorts out the desk and dusts the bookshelves and dumps the dreams in the trash. We go around with this tacit agreement that dreams are mostly meaningless, yet the brain keeps making them; and we go to bed knowing that we'll go a bit insane but that it's no big deal, really, that in the morning breakfast and a shower will set us right again. And it does.

Yet in the Body Snatchers stories, sleep doesn't make people temporarily insane; it makes them perfectly and utterly sane, endlessly and coldly logical. It destroys the identity in a more permanent way; falling asleep leads to being replaced by an alien being who has all the same memories but none of the emotion. The consciousness is transfered to another body, the humanity left behind somewhere in the gray fluff, to be swept away and thrown in the trash.

The stories feature alien characters encouraging humans to quit struggling, to give up and accept their fate. It's a conversation that enhances the horror and the sense of betrayal: former friends have changed--changed horribly--and don't mind at all; in fact they want us to join them. Given that humans are fond of thinking that emotions are distinctly human (a dodgy proposition given the evidence that dogs, primates, and countless other mammals show grief, insecurity, jealousy, and indignation), the stories can also be read as an exploration of the fear of evolution. The pods are much more efficient at reproducing than humans are, and they seem to get along much better; and in each version of the story the chances of human survival begin to look slim. Perhaps each story is asking if it's not merely an accident that humans have reigned so long, and if we truly deserve our self-proclaimed perch at the top. If so, it's no surprise that the stories have proved enduringly horrifying.

Labels: about fiction, blues, body snatchers, horror, movies, RnB

body snatchers mix, part 1

So I've made a Body Snatchers mix which I'll be posting over the next week and a half or so.

Harold Melvin & The Blue Notes -- Wake Up Everybody

Philly soul wearing its heart on its sleeve, confident in its sincerity and optimism and urging positive change. Sing it, Teddy.

The Beatles -- I'm Looking Through You (alt version)

This one is probably one of the most thematically related to the Body Snatchers stories, though written for quite different reasons: "I'm looking through you / where did you go? / I thought I knew you / What did I know? / You don't look different but you have changed / I'm looking through you; you're not the same." It's the alt take off Anthology 2, naturally enough, and it says something for the general quality of the Beatles' work that for most bands this version would have been a perfectly acceptable release.

Sam Roberts -- Paranoia

Radio-friendly pop-rock, the kind of track I wouldn't usually post, but there's something about this one that keeps bringing me back to it. Maybe it's the ooooooohs.

[If You Don't Know Me by Now: The Best of Harold Melvin & the Blue Notes ]

[Anthology 2]

[We Were Born in a Flame]

A brief philosophy of horror fiction: horror is deliberately transgressive and cheerfully untactful; it's not interested in chitchat about the weather, instead it wants to talk (metaphorically, or literally) about taboos. A good horror writer is like a tough-love psychiatrist, finding our most vulnerable spots and prodding them; the horror story is like Ingmar Bergman with optional religious iconography, yet it has no pre-defined point of view and no social obligations beyond investigating and reporting. It may or may not advocate social revolution and may even be reactionary--Night of the Living Dead is not advocating cannibalism; Frankenstein would be a poor witness for science--but it's speculative fiction and it must address taboos, regardless of whether doing so will shock any of the audience.

It's probably an oversimplification to say that horror fiction is about death, since there are some perfectly horrifying horror stories in which no one dies and since, in any case, death is the result of vulnerability. Yet "vulnerability" covers a lot of ground: it's a theme common to the shower scene, being lost in the woods, being chased by a plane, and having an eyeball sliced with a razor.

Of all the kinds of vulnerability, there are a number of horror films about a threat to current identity, about the threat of continuing life in a radically different form: films as diverse as Dracula, The Howling, and Night of the Living Dead; The Fly, The Thing, and The Exorcist; Misery, Rosemary's Baby, and The Invasion of the Body Snatchers.

The ghost, vampire, werewolf, and zombie films have centuries of legends behind them and have the most variants as a result, but Invasion of the Body Snatchers gives a fair showing considering its relative youth. The story was first serialized in Collier's in late 1954 under the title Body Snatchers; Jack Finney expanded it and rewrote the ending for publication as a novel in 1955, and the book was republished with more trivial changes in 1978. As of 2006 the story has had three authorized film versions (with four different endings among them); a fourth film version was finished in October 2006 but was rewritten so much after the novel was optioned that the producers decided it was not actually a version of Finney's work.

All these stories--the body snatchers and the rest--are fertile soil for a writer (any writer, including satirists like Terry Pratchett and the Futurama crew) and are firmly a part of the culture. But what do they mean as cultural artefacts? What do they say about the environment they were made in; what kinds of changes did people fear, and what cultural and historical backgrounds help explain those fears?

I doubt I'll find the answer to all of these questions, but in exploring them I can at least see what other questions crop up along the way. So. The start of the Body Snatchers mix. More later on Finney's three versions, Siegel's two versions, Kaufman's 1978 film, and Ferrara's 1993 film.

Labels: about fiction, body snatchers, horror, movies, RnB, rock