Friday, June 29, 2007:

What kind of slide does Jimmie Davis use? It's not a knife on electric guitar, aggressive, thick, chunky, distorted. It's not a knife on electric guitar, gruff and impetuous, with a sense of timing all its own, dropping flats and sharps in where it pleases. It's not a dobro, not a lap steel, not a sonic papaya smoothie. It's not medicine bottle on nylon; it doesn't sound like Valium on dreamscape lullaby.

No, it's got a slight bite to it and it's played with finesse. It's a sweet and durable melody, even if the lyrics (like Davis' politics) haven't aged well.

[Available on a number of albums, including The Voice Of The Blues: Bottleneck Guitar Masterpieces and The Roots of Rap.]

Hum Dum Dinger

Jimmie Davis -- She's a Hum Dum Dinger From DingersvilleWhat kind of slide does Jimmie Davis use? It's not a knife on electric guitar, aggressive, thick, chunky, distorted. It's not a knife on electric guitar, gruff and impetuous, with a sense of timing all its own, dropping flats and sharps in where it pleases. It's not a dobro, not a lap steel, not a sonic papaya smoothie. It's not medicine bottle on nylon; it doesn't sound like Valium on dreamscape lullaby.

No, it's got a slight bite to it and it's played with finesse. It's a sweet and durable melody, even if the lyrics (like Davis' politics) haven't aged well.

[Available on a number of albums, including The Voice Of The Blues: Bottleneck Guitar Masterpieces and The Roots of Rap.]

Labels: country blues

Wednesday, December 13, 2006:

And the pods march on: next: Kaufman, Ferrara, closing thoughts. You're liking the music at least, I hope.

Howard Tate -- Hold Me Tight

Atypical reggae-inflected soul from Howard Tate.

[Howard Tate's Reaction ]

Otis Rush -- My Love Will Never Die (solo take with piano)

This is a slow, somber take, with Rush apparently still trying to figure out whether the song was meant to be a dirge. The occasional laughter in the background, and Rush's own laughter at the end, suggests that maybe it wasn't.

[Mr. Dixon's Workshop]

Otis Rush -- My Love Will Never Die

Otis Rush tries again, giving the song a lurching rhythm, trilling piano, guitar lines that are sinuous and somehow yearning, and banshee-like vocals leaving no doubt about the pain.

[Essential Collection: The Classic Cobra Recordings 1956-1958]

Magic Sam -- My Love Will Never Die

Magic Sam taking an approach very similar to Otis Rush's, ten years after. Sam and Rush were both on Cobra; West Side Soul is one of the classic blues records. (Interestingly enough, Sam used to play with fellow Chicagoan Syl Johnson in the 50s.)

[West Side Soul]

Dallas String Band -- So Tired

I think it might be easy to take this song ironically, but I love it: the washboard, the fretwork, the melody, the harmony, the progression. And the lyrics, at least what I can make out of them: "So tired of crying / so tired of sighing / so tired of being alone" ... "Though we are drifting far apart / My arms are empty but never my heart / So tired of yearning / For your returning / So tired of waiting for you."

[Texas Black Country Dance Music (1927-1935) @ emusic]

Kay Star -- So Tired

Another one you could take ironically, I guess, but I'm not hip enough to do it. I like the song; I hear something in the vocals that's anachronistic; I can't pinpoint it or explain it, but I like it. It's a very sweet song, uncomplicated and sincere.

[Kay Starr: the Best of The Standard Transcriptions @ emusic]

Junior Wells -- So Tired

Very murky sound on this one, no doubt on purpose--it's like the aural equivalent of squelching your way through thick dark muck that keeps trying to eat your shoes. Wonderful song, though, and the blues were meant to be at least a little discontent.

[1957-1966]

Eddie Bo -- I'm So Tired

Gritty early R&B, Bo rolling out piano riffs and howling about love given in vain.

[I Love to Rock 'N' Roll ]

(Ongoing spoiler warning: texts and films, including endings, discussed below.)

Siegel's 1956 filming of The Body Snatchers hews closely to the established text for most of the film: the story still deals with Miles, Becky, Jack, and Theodora (now called "Teddy"); and Miles' friend the pyschiatrist (now called "Danny" rather than "Mannie"). Miles was divorced more recently than in the book (five months rather than five years) and Becky more recently still (the weekend before the start of the story). As in the book, they had dated each other prior to marrying someone else, and, as in the book, they find themselves falling in love again after the divorces. Early in the film, after scattered reports of people feeling that their family members weren't themselves, Miles jokes that he'd hate to wake up and find that Becky wasn't Becky.

"I'm not the high school kid you used to romance," Becky says, "so how could you tell?"

"You really want to know?" he says. Becky does, so he kisses her.

The film has its differences, though, some of them interesting and others less so, and a few just as inconclusive as the differences among the Finney versions. In Siegel's film, Miles' self-doubts are greatly diminished and the concern over neighborhood upkeep almost entirely eliminated; the only mention of anything decrepit is near the beginning as Miles is driving into town from the train station: he nearly runs over Jimmy Grimaldi, the young son of farmers who have recently closed their vegetable stand.

The film follows Miles, Becky, Jack, and Teddy as they begin to suspect that the people claiming the impossible are in fact correct. Halfway through the film, Miles discovers four pods in his greenhouse, splitting open and beginning to look human. Miles urges Jack and Teddy to leave for help, and Becky tries to phone the FBI as Miles tries and fails to dispatch all the pods in the greenhouse. He lingers, pitchfork in hand, over the one turning into Becky, then decides he can't kill it and instead kills the one turning into him.

Outside town, desperate for somewhere to go for help, Miles drives to his receptionist's house, where he overhears some chilling dialogue:

"Baby asleep yet, Sally?"

"Not yet, but she will be soon, and there'll be no more tears."

Hiding in his office with Becky, Miles delivers the director's message:

"In my practice I've seen people who've allowed their humanity to drain away. Only it happened slowly instead of all at once. They didn't seem to mind."

"Just some people, Miles."

"All of us. A little bit. We harden our hearts, grow callous--only when we have to fight to stay human do we realize how precious it is to us, how dear--as you are to me."

In the morning they see trucks arrive on the plaza and the tarps pulled back, the trucks full of pods. The townspeople collect pods and take them to their cars for distribution. When Jack arrives, their relief is quickly crushed: he's been changed into a pod person; and Danny was one all along. They explain the alien origins of the pods and explain what it's like to be a pod person:

In the morning they see trucks arrive on the plaza and the tarps pulled back, the trucks full of pods. The townspeople collect pods and take them to their cars for distribution. When Jack arrives, their relief is quickly crushed: he's been changed into a pod person; and Danny was one all along. They explain the alien origins of the pods and explain what it's like to be a pod person:

Miles: "I love Becky. Tomorrow will I fell the same?"

Danny shakes his head. "There's no need for love."

"No emotion? Then you have no feelings? Only the instinct to survive. You can't love or be loved, am I right?"

"You say it as if it were terrible; believe me, it isn't. You've been in love before; it didn't last. It never does. Love. Desire. Ambition. Faith. Without them life's so simple, believe me."

And as if one betrayal were not enough, there's the climax of the film: Miles and Becky, exhausted, on the run from the entire town, just like in the book. Except they hide in a tunnel under some slats, rather than under some brush in the fields, and Miles leaves Becky to investigate some beautiful music which Becky says must mean that someone still knows what love is. When he returns he finds Becky in a different location; she's too tired to walk so Miles picks her up and begins to walk out of the tunnel. He trips and they fall into a mud puddle, where they kiss, and Siegel springs a surprise on a 1950s audience familiar with the source material: Becky looks up at Miles exceptionally coolly; Miles pulls away, face registering alarm and disgust. She's been changed. She tells him it's not painful, and he should quit resisting; then as he flees she shouts at the others that he's there.

They let him go to the highway, where he is taken for a drunk or a maniac; he finds the back of a semi loaded with pods and then, on the street, continues to shout his warnings into the camera: "They're coming! You're next!"

And there it would have ended, except that the film tested poorly and the studio forced a change. So Siegel shot a pair of tacky bookends: starting the film with a psychiatrist arriving at a hospital to find Miles panicked and unconvincing; and ending the film with the psychiatrist leaving the room and encountering a truck driver being pushed in on a gurney, with a broken arm and two broken legs. The psychiatrist is informed that the man ran a red light and crashed into a bus, tipping his truck over and spilling a cargo of large and unusual things that look like seed pods. So he goes to the phone, where he shouts at the operator to get him the FBI right away, and yes it's an emergency. And there the film ends.

It's a strange ending for a number of reasons. Generally it's accepted as an inferior ending to the one Siegel intended, which was to leave Miles looking like a stark raving lunatic on the freeway. The new ending might be considered a challenge to the auteur theory in that the studio forced Siegel to add it, against Siegel's wishes. Yet it's also somewhat appropriate in that the new ending hews more closely to the ending to the serial originally optioned: invoking the federal government to come solve local problems with national implications. And yet it's also a sly ending, a subtly suversive ending, on Siegel's part: the pyschiatrist believes Miles and calls for help. "Excellent," we think. "The day is saved." Except we see "The End" before we hear what happens next, and so it's easy to forget that Miles also tried to call for help, and that he could not get through because the pod people already controlled the phone system.

Besides, I'm not sure how many people the new ending relly convinced: I saw the film as a child and didn't see it for a decade afterwards; what I remembered of it was not the call to the FBI but Danny's betrayal and the unveiling of the truck loaded with pods.

In some ways Siegel's The Invasion of the Body Snatchers reminds me of Howard Hawk's The Thing: both deal with an alien invasion of murderous perambulatory plant matter; but The Thing has no patience for the federal government or the visitor, and The Invasion of the Body Snatchers takes a more patient, cautious, watchful stance. There's probably fertile soil there for someone willing to argue that the two films are the Rio Bravo and High Noon of science fiction.

It's common to put Finney's novel and Siegel's film into a Cold War context, and Glen M. Johnson does it as well as anyone. A bit from "'We'd Fight .... We Had to': The Body Snatchers as Novel and Film":

At the time of the stories' publication, HUAC's investigation into Communist propaganda in Hollywood, followed by its blacklist of the Hollywood Ten in 1947, was not yet ten years past. Joe McCarthy had spent several years in Congress making rabid declamations against suspected communists as chair of the Subcommittee on Investigations, and only in late 1954, after several years of bellicose and frequently baseless accusations, had he netted a formal censure in the Senate. It's easy to imagine that the alien invasion in the body snatchers stories serves as a metaphor for Cold War anxieties--either as a fear of communism or as a fear of McCarthyism. If there's one thing central to U.S. belief it's rugged individualism, and both sides were no doubt feeling an overwhelming pressure to conform. So it's somewhat common that the series of betrayals in the story, executed by family and friends, reminds people (ironically or not) of J. Edgar Hoover's sensationalist warning in Masters of Deceit that "there are thousands of people in this country now working in secret to make it happen here." Furthermore, it's easy to view the sleep metaphor as freighted with political baggage, especially given the "sleep no more" propaganda common during the Cold War.

Yet as J. Hoberman notes in "Paranoia and the Pods,"

Siegel, for his part, seems content to think of the film as about conformity in general: "It's the same as people who wlecome going into the army or prison. There's regimentation, a lack of having to make up your own mind, face decisions.... People are becoming vegetables. I don't know what the answer is, except an awareness of it. That's what makes a picture like Invasion of the Body Snatchers so important." (Parkes, "There Will Be No Survivors")

And Finney denies all of these interpretations, both here and elsewhere:

And, too, it's obvious that the reader (or viewer) must understand, process, and interpret the parts of a story for it to have any meaning. Those interpretations are necessarily personal affairs, at times idiosyncratic or conflicted but always dependent on associations with existing knowledge. Is the story about communism? McCarthyism? The Red Scare? The case for each of those could be made, sure, and frequently is. Art is largely an interpretive matter and almost never yields as unequivocal results as math. And should it?

body snatchers mix, part 4

And the pods march on: next: Kaufman, Ferrara, closing thoughts. You're liking the music at least, I hope.

Howard Tate -- Hold Me Tight

Atypical reggae-inflected soul from Howard Tate.

[Howard Tate's Reaction ]

Otis Rush -- My Love Will Never Die (solo take with piano)

This is a slow, somber take, with Rush apparently still trying to figure out whether the song was meant to be a dirge. The occasional laughter in the background, and Rush's own laughter at the end, suggests that maybe it wasn't.

[Mr. Dixon's Workshop]

Otis Rush -- My Love Will Never Die

Otis Rush tries again, giving the song a lurching rhythm, trilling piano, guitar lines that are sinuous and somehow yearning, and banshee-like vocals leaving no doubt about the pain.

[Essential Collection: The Classic Cobra Recordings 1956-1958]

Magic Sam -- My Love Will Never Die

Magic Sam taking an approach very similar to Otis Rush's, ten years after. Sam and Rush were both on Cobra; West Side Soul is one of the classic blues records. (Interestingly enough, Sam used to play with fellow Chicagoan Syl Johnson in the 50s.)

[West Side Soul]

Dallas String Band -- So Tired

I think it might be easy to take this song ironically, but I love it: the washboard, the fretwork, the melody, the harmony, the progression. And the lyrics, at least what I can make out of them: "So tired of crying / so tired of sighing / so tired of being alone" ... "Though we are drifting far apart / My arms are empty but never my heart / So tired of yearning / For your returning / So tired of waiting for you."

[Texas Black Country Dance Music (1927-1935) @ emusic]

Kay Star -- So Tired

Another one you could take ironically, I guess, but I'm not hip enough to do it. I like the song; I hear something in the vocals that's anachronistic; I can't pinpoint it or explain it, but I like it. It's a very sweet song, uncomplicated and sincere.

[Kay Starr: the Best of The Standard Transcriptions @ emusic]

Junior Wells -- So Tired

Very murky sound on this one, no doubt on purpose--it's like the aural equivalent of squelching your way through thick dark muck that keeps trying to eat your shoes. Wonderful song, though, and the blues were meant to be at least a little discontent.

[1957-1966]

Eddie Bo -- I'm So Tired

Gritty early R&B, Bo rolling out piano riffs and howling about love given in vain.

[I Love to Rock 'N' Roll ]

(Ongoing spoiler warning: texts and films, including endings, discussed below.)

Siegel's 1956 filming of The Body Snatchers hews closely to the established text for most of the film: the story still deals with Miles, Becky, Jack, and Theodora (now called "Teddy"); and Miles' friend the pyschiatrist (now called "Danny" rather than "Mannie"). Miles was divorced more recently than in the book (five months rather than five years) and Becky more recently still (the weekend before the start of the story). As in the book, they had dated each other prior to marrying someone else, and, as in the book, they find themselves falling in love again after the divorces. Early in the film, after scattered reports of people feeling that their family members weren't themselves, Miles jokes that he'd hate to wake up and find that Becky wasn't Becky.

"I'm not the high school kid you used to romance," Becky says, "so how could you tell?"

"You really want to know?" he says. Becky does, so he kisses her.

The film has its differences, though, some of them interesting and others less so, and a few just as inconclusive as the differences among the Finney versions. In Siegel's film, Miles' self-doubts are greatly diminished and the concern over neighborhood upkeep almost entirely eliminated; the only mention of anything decrepit is near the beginning as Miles is driving into town from the train station: he nearly runs over Jimmy Grimaldi, the young son of farmers who have recently closed their vegetable stand.

The film follows Miles, Becky, Jack, and Teddy as they begin to suspect that the people claiming the impossible are in fact correct. Halfway through the film, Miles discovers four pods in his greenhouse, splitting open and beginning to look human. Miles urges Jack and Teddy to leave for help, and Becky tries to phone the FBI as Miles tries and fails to dispatch all the pods in the greenhouse. He lingers, pitchfork in hand, over the one turning into Becky, then decides he can't kill it and instead kills the one turning into him.

Outside town, desperate for somewhere to go for help, Miles drives to his receptionist's house, where he overhears some chilling dialogue:

"Baby asleep yet, Sally?"

"Not yet, but she will be soon, and there'll be no more tears."

Hiding in his office with Becky, Miles delivers the director's message:

"In my practice I've seen people who've allowed their humanity to drain away. Only it happened slowly instead of all at once. They didn't seem to mind."

"Just some people, Miles."

"All of us. A little bit. We harden our hearts, grow callous--only when we have to fight to stay human do we realize how precious it is to us, how dear--as you are to me."

In the morning they see trucks arrive on the plaza and the tarps pulled back, the trucks full of pods. The townspeople collect pods and take them to their cars for distribution. When Jack arrives, their relief is quickly crushed: he's been changed into a pod person; and Danny was one all along. They explain the alien origins of the pods and explain what it's like to be a pod person:

In the morning they see trucks arrive on the plaza and the tarps pulled back, the trucks full of pods. The townspeople collect pods and take them to their cars for distribution. When Jack arrives, their relief is quickly crushed: he's been changed into a pod person; and Danny was one all along. They explain the alien origins of the pods and explain what it's like to be a pod person:Miles: "I love Becky. Tomorrow will I fell the same?"

Danny shakes his head. "There's no need for love."

"No emotion? Then you have no feelings? Only the instinct to survive. You can't love or be loved, am I right?"

"You say it as if it were terrible; believe me, it isn't. You've been in love before; it didn't last. It never does. Love. Desire. Ambition. Faith. Without them life's so simple, believe me."

And as if one betrayal were not enough, there's the climax of the film: Miles and Becky, exhausted, on the run from the entire town, just like in the book. Except they hide in a tunnel under some slats, rather than under some brush in the fields, and Miles leaves Becky to investigate some beautiful music which Becky says must mean that someone still knows what love is. When he returns he finds Becky in a different location; she's too tired to walk so Miles picks her up and begins to walk out of the tunnel. He trips and they fall into a mud puddle, where they kiss, and Siegel springs a surprise on a 1950s audience familiar with the source material: Becky looks up at Miles exceptionally coolly; Miles pulls away, face registering alarm and disgust. She's been changed. She tells him it's not painful, and he should quit resisting; then as he flees she shouts at the others that he's there.

They let him go to the highway, where he is taken for a drunk or a maniac; he finds the back of a semi loaded with pods and then, on the street, continues to shout his warnings into the camera: "They're coming! You're next!"

And there it would have ended, except that the film tested poorly and the studio forced a change. So Siegel shot a pair of tacky bookends: starting the film with a psychiatrist arriving at a hospital to find Miles panicked and unconvincing; and ending the film with the psychiatrist leaving the room and encountering a truck driver being pushed in on a gurney, with a broken arm and two broken legs. The psychiatrist is informed that the man ran a red light and crashed into a bus, tipping his truck over and spilling a cargo of large and unusual things that look like seed pods. So he goes to the phone, where he shouts at the operator to get him the FBI right away, and yes it's an emergency. And there the film ends.

It's a strange ending for a number of reasons. Generally it's accepted as an inferior ending to the one Siegel intended, which was to leave Miles looking like a stark raving lunatic on the freeway. The new ending might be considered a challenge to the auteur theory in that the studio forced Siegel to add it, against Siegel's wishes. Yet it's also somewhat appropriate in that the new ending hews more closely to the ending to the serial originally optioned: invoking the federal government to come solve local problems with national implications. And yet it's also a sly ending, a subtly suversive ending, on Siegel's part: the pyschiatrist believes Miles and calls for help. "Excellent," we think. "The day is saved." Except we see "The End" before we hear what happens next, and so it's easy to forget that Miles also tried to call for help, and that he could not get through because the pod people already controlled the phone system.

Besides, I'm not sure how many people the new ending relly convinced: I saw the film as a child and didn't see it for a decade afterwards; what I remembered of it was not the call to the FBI but Danny's betrayal and the unveiling of the truck loaded with pods.

In some ways Siegel's The Invasion of the Body Snatchers reminds me of Howard Hawk's The Thing: both deal with an alien invasion of murderous perambulatory plant matter; but The Thing has no patience for the federal government or the visitor, and The Invasion of the Body Snatchers takes a more patient, cautious, watchful stance. There's probably fertile soil there for someone willing to argue that the two films are the Rio Bravo and High Noon of science fiction.

It's common to put Finney's novel and Siegel's film into a Cold War context, and Glen M. Johnson does it as well as anyone. A bit from "'We'd Fight .... We Had to': The Body Snatchers as Novel and Film":

Finney complicates the simplistic them-vs-us forumula by making his invaders invisible--a force or consciousness that conquers by taking over the minds and personalities of ordinary people. So the "body" snatchers become apt symbols for ideological subversion, fear of which was a characterisitc form of anxiety in the American fifties.Johnson, like many authors discussing the story's Cold War origins, mentions brainwashing: "it is suggestive that The Body Snatchers is set in August 1953, immediately after the Korean armistice, when American newspapers were full of incredulous reports about the 'turncoats' who chose Communism over a return home."

At the time of the stories' publication, HUAC's investigation into Communist propaganda in Hollywood, followed by its blacklist of the Hollywood Ten in 1947, was not yet ten years past. Joe McCarthy had spent several years in Congress making rabid declamations against suspected communists as chair of the Subcommittee on Investigations, and only in late 1954, after several years of bellicose and frequently baseless accusations, had he netted a formal censure in the Senate. It's easy to imagine that the alien invasion in the body snatchers stories serves as a metaphor for Cold War anxieties--either as a fear of communism or as a fear of McCarthyism. If there's one thing central to U.S. belief it's rugged individualism, and both sides were no doubt feeling an overwhelming pressure to conform. So it's somewhat common that the series of betrayals in the story, executed by family and friends, reminds people (ironically or not) of J. Edgar Hoover's sensationalist warning in Masters of Deceit that "there are thousands of people in this country now working in secret to make it happen here." Furthermore, it's easy to view the sleep metaphor as freighted with political baggage, especially given the "sleep no more" propaganda common during the Cold War.

Yet as J. Hoberman notes in "Paranoia and the Pods,"

Sorting out the politics of the men who filmed Invasion of the Body Snatchers is not easy. Siegel has described himself as a liberal, although his ouevre is more suggestive of a libertarian belief in rugged individualism. Wanger, a producer with an interest in topically political material, was responsible for both the crypto-fascist Gabriel over the White House (1933) and the prematurely anti-fascist Blockade (1938) as well as for such New Dealish genre exercises as You Only Live Once, Stagecoach, and Foreign Correspondent.Hoberman goes on to note that Mainwaring, the film's screenwriter, had written the "relentlessly perfunctory" anti-communist film A Bullet for Joey and that Invasion of the Body Snatchers' script was rewritten by Richard Collins, "a former Communist Party functionary, co-author of the once notorious Song of Russia (1943), [and] an announced unfriendly witness first subpoenaed by the House Un-American Activities Committee in autumn 1947 among the original Hollywood Nineteen" who later turned witness for the FBI. So the film might be read as an anti-Communist fable, or as a satire of McCarthyism, or simply as a richly metaphorical work authored by a number of men with strikingly different philosophies.

Siegel, for his part, seems content to think of the film as about conformity in general: "It's the same as people who wlecome going into the army or prison. There's regimentation, a lack of having to make up your own mind, face decisions.... People are becoming vegetables. I don't know what the answer is, except an awareness of it. That's what makes a picture like Invasion of the Body Snatchers so important." (Parkes, "There Will Be No Survivors")

And Finney denies all of these interpretations, both here and elsewhere:

For years now, I've been amused by the fairly widely held notion that The Body Snatchers has anything to do with the cold war, McCarthyism, conformity... It does not. I was simply intrigued by the notion of a lot of people insisting that their friends and relatives were impostors.

--"Paranoia and the Pods," Sight and Sound May 1994, p.31

I have read explanations of the "meaning" of this story, which amuse me, because there is no meaning at all; it was just a story meant to entertain, and with no more meaning than that. The first movie version of the book followed the book with great faithfulness, except for the foolish ending; and I've always been amused by the contentions of people connected with the picture that they had a message of some sort in mind. If so, it's a lot more than I ever did, and since they followed my story very closely, it's hard to see how this message crept in. And when the message has been defined, it has always seemed a little simple-minded to me. The idea of writing a whole book in order to say that it's not really a good thing for us all to be alike, and that individuality is a good thing, makes me laugh.So the question is, then, whether the author is the final word on what a text means. I think the author often has a good idea of what he intended, except that even he might not realize all of the intentions and subtleties: I'm reminded of Ray Bradbury's comment in the afterword for Fahrenheit 451 that for decades he didn't notice that Faber was the name of a pencil company and that Montag was the name of a paper company.

--personal letter to Stephen King, December 24, 1979, as cited in Danse Macabre, 1983 Berkeley paperback, p. 306-307

And, too, it's obvious that the reader (or viewer) must understand, process, and interpret the parts of a story for it to have any meaning. Those interpretations are necessarily personal affairs, at times idiosyncratic or conflicted but always dependent on associations with existing knowledge. Is the story about communism? McCarthyism? The Red Scare? The case for each of those could be made, sure, and frequently is. Art is largely an interpretive matter and almost never yields as unequivocal results as math. And should it?

Labels: blues, body snatchers, country blues, horror, movies, RnB, vocal

Tuesday, December 12, 2006:

Some more songs tangentially related to the Body Snatchers stories, and more about the stories (with spoilers) below that:

Jimmy Bo Horne -- Get Happy

There's something here that reminds me of much of George McCrae's work, probably in the simple composition and the repetition, but also in the reliance on a sweet hook and an energetic horn section in a poppy R&B track with high-flying vocals. Another happy song, appropriately enough.

[The Legendary Henry Stone Presents: Jimmy Bo Horne @ emusic or @ amazon]

Shirley Bassey -- Hey Big Spender (Wild Oscar mix)

Bassey likes to make these big brassy music numbers that go well with Bond films (Goldfinger, Moonraker, Diamonds are Forever) and that get a deft parody in The Life of Brian ("He had arms ... and legs ... and hands ... and feet / This boy whose name was Brian"). The remix here decides that brassy isn't brassy enough, and so kicks it up a notch: adding breakneck percussion, muted guitar, vocal effects, and tempo changes.

[Shirley Bassey - The Greatest Hits]

J.J. Cale -- Call the Doctor

Countrified blues-rock, subdued delivery, plodding bass, sour horns, and electric guitar swelling into a stoned melancholy solo. The description sounds horrible but Cale pulls it off somehow.

[Naturally]

Eddie Floyd -- Bring It on Home To Me

Easy-going R&B, not pining, not pleading, not arguing a case so much as pointing out what a good time you could be having--hoping you'll come to your senses and come join in.

[Eddie Floyd - Chronicle: Greatest Hits]

Lou Rawls -- Bring It on Home

Nevermind the showboating at the beginning; give the song a minute (actually, 45 seconds). Let the bass come in and the funk get dropped; let Lou gather his evidence and practice his line of argument. It's a smooth-talking dapper performance, pitch-perfect and with just enough edge on it to let you know he's serious, but not so serious as to keep the jurors from clapping.

[Anthology]

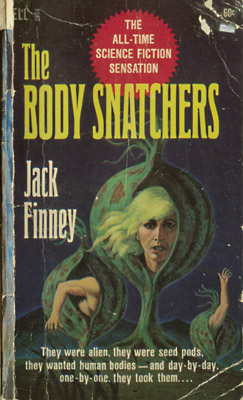

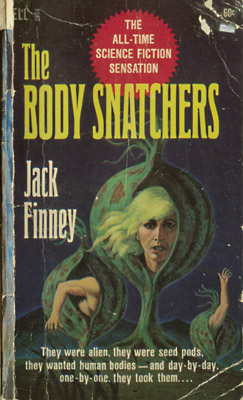

Jack Finney has published at least three different versions of Body Snatchers: first as serialized in Collier's in November and December 1954, then as a book in 1955 (expanded and given a different climax) and then with further edits in 1978 to coincide with Philip Kaufman's second film version of the story.

The three have strong similarities, as could be expected. The text versions take place in Santa Mira, a small town outside San Francisco, and feature a doctor named Miles Bennell, a former flame named Becky Driscoll, a psychologist friend named Mannie Kaufman, a writer friend named Jack Belicec, and his wife Theodora. At the start of the story, Becky approaches Miles and tells him of her cousin Wilma who's become convinced that her Uncle Ira is not actually Uncle Ira; when they visit Wilma, she explains that her aunt hasn't noticed because she is also not her aunt. From there the details accrue suggesting that the humans are being besieged by aliens intent on replacing them, and the small group of humans decide to fight.

Along the way Becky and Miles, both divorced, find themselves increasingly attracted to each other. Becky has divorced recently and Miles five years earlier, yet Miles continues to be bothered by his divorce, taking it as a sign of some shameful defeat. There are scattered mentions throughout the novel, most of them wry, and others which seem either self-deluding or callous and sexist:

So early on Miles seems like a big spender, maybe a bit arrogant, maybe living a lavish lifestyle, with no time for Becky. In the 1978 version the passage is changed: "I drive a 1973 Mercedes two-seater, a nice fire-engine red job, bought used, to maintain the popular illusion that all doctors are rich." (Finney '78, p. 13)

Yet most of the differences between the two versions are subtle, perhaps inconsequential--instead of golf and swimming, Miles plays tennis, things like that. (In fact, the two versions seem so similar that the cynic in me suggests that the 1978 revisions were published simply to allow an extension on the copyright--copyright terms at the time were much more limited and the one on Body Snatchers had nearly run out.)

In the two novel versions Miles, Becky, Jack, and Theodora are increasingly persecuted, then flee town only to find that they don't know where to go or what to do. So they return to town, where they are split up. Becky and Miles hide in a field just outside town--the field where, it turns out, a professor had discovered what he thought was most likely an alien plant, and then a few days later retracted his story. It is here where the aliens are growing their pods for distribution, and Miles and Becky make a desperate last stand, setting fire to the fields and smashing pods. The aliens recognize their defeat and the pods detach from the plants, fly up off the ground, and leave the planet. Miles and Becky reunite with Jack and Theodora and discover that the aliens have a curiously short lifespan; most of them die off within a few years.

The serial version is apparently much different: Robert Shelton in "Genre and Closure in the Seven Versions of Invasion of the Body Snatchers" mentions that the 1955 Dell paperback "is based on, and twice the length of, the serial" and that "in the 1954 serial, a posse of FBI agents armed with 'riot guns' and 'small, light, almost dainty-looking machine guns'" arrives on site, attracted by Miles' fire, and helps fend off the alien invasion.

What does it mean that the endings are so different? What point was Finney trying to make, or deciding not to make? Catherine Jurca, in "Of Satire and Sofas," calls the novel "an allegory of postwar suburbanisation," yet the article is too brief to offer much supporting evidence and it's left to the reader to remember the United States' postwar population boom and the move from the cities to the suburbs.

Michael Parkes, in "There Will Be No Survivors," takes the novel as a metaphor for a different kind of encroaching conformity, and the pods as representing a different threat to identity: the introduction of television into American culture. Parkes notes that "between 1948 and 1955, television was installed in nearly two-thirds of the nation's homes and became the mythic and ideological unifier of the fragmented post-war family" and served "as a sign of suburban achievement," yet one that moved the family away from the hearth and conversation to the television and silent viewing. Parkes notes the effect of television on bars and cafes, as well, and its corollary to the cafe scene in the novel when Miles and Becky go to the Sky Terrace in the Siegel film to find few customers and no live music, but instead a jukebox: "the artistry and individuality of the original band has been 'snatched' and replaced by an inferior technological substitute." In this reading, Parkes considers the story's message somewhat ironic, calling it "an anti-media discourse which in itself is contradictory, as the film [and book] itself exists within the media."

This interpretation of the book as an anti-media, Luddite response to technological innovation is interesting; yet by far the most common reading of the story is as a metaphor for the political climate in the United States during the Cold War--whether as one about McCarthyism or as one about the Red Scare. More on that, and on Finney's and Siegel's reactions to it, next post.

body snatchers mix, part 3

Some more songs tangentially related to the Body Snatchers stories, and more about the stories (with spoilers) below that:

Jimmy Bo Horne -- Get Happy

There's something here that reminds me of much of George McCrae's work, probably in the simple composition and the repetition, but also in the reliance on a sweet hook and an energetic horn section in a poppy R&B track with high-flying vocals. Another happy song, appropriately enough.

[The Legendary Henry Stone Presents: Jimmy Bo Horne @ emusic or @ amazon]

Shirley Bassey -- Hey Big Spender (Wild Oscar mix)

Bassey likes to make these big brassy music numbers that go well with Bond films (Goldfinger, Moonraker, Diamonds are Forever) and that get a deft parody in The Life of Brian ("He had arms ... and legs ... and hands ... and feet / This boy whose name was Brian"). The remix here decides that brassy isn't brassy enough, and so kicks it up a notch: adding breakneck percussion, muted guitar, vocal effects, and tempo changes.

[Shirley Bassey - The Greatest Hits]

J.J. Cale -- Call the Doctor

Countrified blues-rock, subdued delivery, plodding bass, sour horns, and electric guitar swelling into a stoned melancholy solo. The description sounds horrible but Cale pulls it off somehow.

[Naturally]

Eddie Floyd -- Bring It on Home To Me

Easy-going R&B, not pining, not pleading, not arguing a case so much as pointing out what a good time you could be having--hoping you'll come to your senses and come join in.

[Eddie Floyd - Chronicle: Greatest Hits]

Lou Rawls -- Bring It on Home

Nevermind the showboating at the beginning; give the song a minute (actually, 45 seconds). Let the bass come in and the funk get dropped; let Lou gather his evidence and practice his line of argument. It's a smooth-talking dapper performance, pitch-perfect and with just enough edge on it to let you know he's serious, but not so serious as to keep the jurors from clapping.

[Anthology]

Jack Finney has published at least three different versions of Body Snatchers: first as serialized in Collier's in November and December 1954, then as a book in 1955 (expanded and given a different climax) and then with further edits in 1978 to coincide with Philip Kaufman's second film version of the story.

The three have strong similarities, as could be expected. The text versions take place in Santa Mira, a small town outside San Francisco, and feature a doctor named Miles Bennell, a former flame named Becky Driscoll, a psychologist friend named Mannie Kaufman, a writer friend named Jack Belicec, and his wife Theodora. At the start of the story, Becky approaches Miles and tells him of her cousin Wilma who's become convinced that her Uncle Ira is not actually Uncle Ira; when they visit Wilma, she explains that her aunt hasn't noticed because she is also not her aunt. From there the details accrue suggesting that the humans are being besieged by aliens intent on replacing them, and the small group of humans decide to fight.

Along the way Becky and Miles, both divorced, find themselves increasingly attracted to each other. Becky has divorced recently and Miles five years earlier, yet Miles continues to be bothered by his divorce, taking it as a sign of some shameful defeat. There are scattered mentions throughout the novel, most of them wry, and others which seem either self-deluding or callous and sexist:

I'd seen Becky at least every other night all the past week, but not because there was any romance building up between us. It was just better than hanging around the pool hall, playing solitaire, or collecting stamps. She was a pleasant, comfortable way of spending some evenings, nothing more, and that suited me fine.Then there's this more telling passage as Miles is shaving:

--Body Snatchers, '55, p. 24

'You handsome bastard,' I said to my face. 'You can marry them, all right; you just can't stay married, that's your trouble. You are weak. Emotionally unstable. Basically insecure. A latent thumb-sucker. A cesspool of immaturity, unfit for adult responsibility." ... I cut it out, and finished shaving with the uncomfortable feeling that for all I knew it wasn't funny but true, that having failed with one woman, I was getting too involved with another, and that for my sake and hers, she should be anywhere but here under my roof.Both the paperback versions share Miles' self-doubt following his divorce, his penchant for prescribing sedatives, his passive wait-and-see attitude in the face of an obviously mounting crisis, and the curious marker of the body-snatched: an indifference to neighborhood upkeep. A visiting salesman complains that it's hard to get into and out of the town; coffee is hard to come by and tastes bad when a restaurant has it; and Miles notes that his Coca-Cola is warm. And outside the restaurant, on a littered street:

--Body Snatchers, '55, p.76

"Miles," she said in a cautious, lowered tone, "am I imagining it, or does this street look--dead?"Of the three versions, the Collier's version is probably the hardest to find: so far as I know it was never collected and published separately without changes, and it doesn't seem to be available in various academic databases, so finding it most likely requires access to the original magazines. I haven't read this version but I have the other two, and they're fairly similar. One of the more striking differences between the two novels happens early on when Miles mentions his car: "I drive a '52 Ford convertible, one of those fancy green ones, because I don't know of any law absolutely requiring a doctor to drive a small black coupé." (Finney '55, p. 13)

I shook my head. "No. In seven blocks we haven't passed a single house with as much as the trim being repainted; not a roof, porch, or even a cracked window being repaired; not a tree, shrub, or a blade of grass being planted, or even trimmed. Nothing's happening, Becky, nobody's doing anything. And they haven't for days, maybe weeks."

--Body Snatchers '55, p. 108

So early on Miles seems like a big spender, maybe a bit arrogant, maybe living a lavish lifestyle, with no time for Becky. In the 1978 version the passage is changed: "I drive a 1973 Mercedes two-seater, a nice fire-engine red job, bought used, to maintain the popular illusion that all doctors are rich." (Finney '78, p. 13)

Yet most of the differences between the two versions are subtle, perhaps inconsequential--instead of golf and swimming, Miles plays tennis, things like that. (In fact, the two versions seem so similar that the cynic in me suggests that the 1978 revisions were published simply to allow an extension on the copyright--copyright terms at the time were much more limited and the one on Body Snatchers had nearly run out.)

In the two novel versions Miles, Becky, Jack, and Theodora are increasingly persecuted, then flee town only to find that they don't know where to go or what to do. So they return to town, where they are split up. Becky and Miles hide in a field just outside town--the field where, it turns out, a professor had discovered what he thought was most likely an alien plant, and then a few days later retracted his story. It is here where the aliens are growing their pods for distribution, and Miles and Becky make a desperate last stand, setting fire to the fields and smashing pods. The aliens recognize their defeat and the pods detach from the plants, fly up off the ground, and leave the planet. Miles and Becky reunite with Jack and Theodora and discover that the aliens have a curiously short lifespan; most of them die off within a few years.

The serial version is apparently much different: Robert Shelton in "Genre and Closure in the Seven Versions of Invasion of the Body Snatchers" mentions that the 1955 Dell paperback "is based on, and twice the length of, the serial" and that "in the 1954 serial, a posse of FBI agents armed with 'riot guns' and 'small, light, almost dainty-looking machine guns'" arrives on site, attracted by Miles' fire, and helps fend off the alien invasion.

What does it mean that the endings are so different? What point was Finney trying to make, or deciding not to make? Catherine Jurca, in "Of Satire and Sofas," calls the novel "an allegory of postwar suburbanisation," yet the article is too brief to offer much supporting evidence and it's left to the reader to remember the United States' postwar population boom and the move from the cities to the suburbs.

Michael Parkes, in "There Will Be No Survivors," takes the novel as a metaphor for a different kind of encroaching conformity, and the pods as representing a different threat to identity: the introduction of television into American culture. Parkes notes that "between 1948 and 1955, television was installed in nearly two-thirds of the nation's homes and became the mythic and ideological unifier of the fragmented post-war family" and served "as a sign of suburban achievement," yet one that moved the family away from the hearth and conversation to the television and silent viewing. Parkes notes the effect of television on bars and cafes, as well, and its corollary to the cafe scene in the novel when Miles and Becky go to the Sky Terrace in the Siegel film to find few customers and no live music, but instead a jukebox: "the artistry and individuality of the original band has been 'snatched' and replaced by an inferior technological substitute." In this reading, Parkes considers the story's message somewhat ironic, calling it "an anti-media discourse which in itself is contradictory, as the film [and book] itself exists within the media."

This interpretation of the book as an anti-media, Luddite response to technological innovation is interesting; yet by far the most common reading of the story is as a metaphor for the political climate in the United States during the Cold War--whether as one about McCarthyism or as one about the Red Scare. More on that, and on Finney's and Siegel's reactions to it, next post.

Labels: about fiction, body snatchers, country blues, horror, RnB, vocal

Friday, September 17, 2004:

Joe McCoy -- If You Take Me Back

Big Joe McCoy was born in Jackson Mississippi in 1905. He was a vocalist and a slide guitarist, and played alone under a number of pseudonyms and with his brother Charlie under a number of different band names. Joe McCoy was for a time married to Memphis Minnie; she's a good musician in her own right, a powerful singer and a talented guitarist, and together they recorded the original "When the Levee Breaks."

I first heard Kansas Joe about ten years ago on a mix tape I got from my ex-girlfriend, under the name "Big Joe and His Washboard Band." At the time I just thought the tape was a nice conciliatory gesture; now I wonder if I was paying attention at all: every song on that tape is about heartbreak. The heartbreak here is offset by the jauntiness: the harmonica, the washboard, the swing feel, the brisk pacing. They all help to put on a strong face, stick out a proverbial chin; but the lyrics give the lie to it, making wild claims, pleading and desperate: "If you take me back I'll buy you a diamond ring / and if you don't, my life don't mean a thing."

A recent posting on The Tofu Hut pointed up the confusion about early blues musicians' names. There's a reason for it: many of them used pseudonyms, and sometimes two different musicians would use the same name.

Who's who

Amazon.com

(Or, if your tolerance for country blues is low,you can try More Music From Northern Exposure. The Les Paul/Mary Ford song on it is very good, but after track #3 I suddenly understood Bob Marley's scorn for Johnny Nash.)

"All I want is your love; you can throw my money away"

First, I'd like to thank The Tofu Hut, Said the Gramophone, Orbis Quintus, Fluxblog, Spoilt Victorian Child, and *sixeyes for the kind words. If you're coming here from somewhere else and you haven't yet checked them out, you should; they're all worth your time. Links on the left are all endorsements, and John at The Tofu Hut has an astonishing blogroll that's worth exploring.Joe McCoy -- If You Take Me Back

Big Joe McCoy was born in Jackson Mississippi in 1905. He was a vocalist and a slide guitarist, and played alone under a number of pseudonyms and with his brother Charlie under a number of different band names. Joe McCoy was for a time married to Memphis Minnie; she's a good musician in her own right, a powerful singer and a talented guitarist, and together they recorded the original "When the Levee Breaks."

I first heard Kansas Joe about ten years ago on a mix tape I got from my ex-girlfriend, under the name "Big Joe and His Washboard Band." At the time I just thought the tape was a nice conciliatory gesture; now I wonder if I was paying attention at all: every song on that tape is about heartbreak. The heartbreak here is offset by the jauntiness: the harmonica, the washboard, the swing feel, the brisk pacing. They all help to put on a strong face, stick out a proverbial chin; but the lyrics give the lie to it, making wild claims, pleading and desperate: "If you take me back I'll buy you a diamond ring / and if you don't, my life don't mean a thing."

A recent posting on The Tofu Hut pointed up the confusion about early blues musicians' names. There's a reason for it: many of them used pseudonyms, and sometimes two different musicians would use the same name.

Who's who

Amazon.com

(Or, if your tolerance for country blues is low,you can try More Music From Northern Exposure. The Les Paul/Mary Ford song on it is very good, but after track #3 I suddenly understood Bob Marley's scorn for Johnny Nash.)

Labels: country blues, personal