Tuesday, December 12, 2006:

Some more songs tangentially related to the Body Snatchers stories, and more about the stories (with spoilers) below that:

Jimmy Bo Horne -- Get Happy

There's something here that reminds me of much of George McCrae's work, probably in the simple composition and the repetition, but also in the reliance on a sweet hook and an energetic horn section in a poppy R&B track with high-flying vocals. Another happy song, appropriately enough.

[The Legendary Henry Stone Presents: Jimmy Bo Horne @ emusic or @ amazon]

Shirley Bassey -- Hey Big Spender (Wild Oscar mix)

Bassey likes to make these big brassy music numbers that go well with Bond films (Goldfinger, Moonraker, Diamonds are Forever) and that get a deft parody in The Life of Brian ("He had arms ... and legs ... and hands ... and feet / This boy whose name was Brian"). The remix here decides that brassy isn't brassy enough, and so kicks it up a notch: adding breakneck percussion, muted guitar, vocal effects, and tempo changes.

[Shirley Bassey - The Greatest Hits]

J.J. Cale -- Call the Doctor

Countrified blues-rock, subdued delivery, plodding bass, sour horns, and electric guitar swelling into a stoned melancholy solo. The description sounds horrible but Cale pulls it off somehow.

[Naturally]

Eddie Floyd -- Bring It on Home To Me

Easy-going R&B, not pining, not pleading, not arguing a case so much as pointing out what a good time you could be having--hoping you'll come to your senses and come join in.

[Eddie Floyd - Chronicle: Greatest Hits]

Lou Rawls -- Bring It on Home

Nevermind the showboating at the beginning; give the song a minute (actually, 45 seconds). Let the bass come in and the funk get dropped; let Lou gather his evidence and practice his line of argument. It's a smooth-talking dapper performance, pitch-perfect and with just enough edge on it to let you know he's serious, but not so serious as to keep the jurors from clapping.

[Anthology]

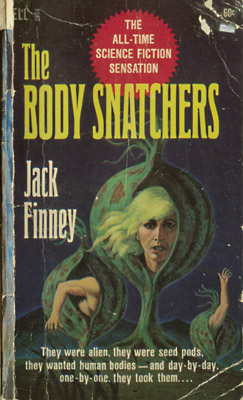

Jack Finney has published at least three different versions of Body Snatchers: first as serialized in Collier's in November and December 1954, then as a book in 1955 (expanded and given a different climax) and then with further edits in 1978 to coincide with Philip Kaufman's second film version of the story.

The three have strong similarities, as could be expected. The text versions take place in Santa Mira, a small town outside San Francisco, and feature a doctor named Miles Bennell, a former flame named Becky Driscoll, a psychologist friend named Mannie Kaufman, a writer friend named Jack Belicec, and his wife Theodora. At the start of the story, Becky approaches Miles and tells him of her cousin Wilma who's become convinced that her Uncle Ira is not actually Uncle Ira; when they visit Wilma, she explains that her aunt hasn't noticed because she is also not her aunt. From there the details accrue suggesting that the humans are being besieged by aliens intent on replacing them, and the small group of humans decide to fight.

Along the way Becky and Miles, both divorced, find themselves increasingly attracted to each other. Becky has divorced recently and Miles five years earlier, yet Miles continues to be bothered by his divorce, taking it as a sign of some shameful defeat. There are scattered mentions throughout the novel, most of them wry, and others which seem either self-deluding or callous and sexist:

So early on Miles seems like a big spender, maybe a bit arrogant, maybe living a lavish lifestyle, with no time for Becky. In the 1978 version the passage is changed: "I drive a 1973 Mercedes two-seater, a nice fire-engine red job, bought used, to maintain the popular illusion that all doctors are rich." (Finney '78, p. 13)

Yet most of the differences between the two versions are subtle, perhaps inconsequential--instead of golf and swimming, Miles plays tennis, things like that. (In fact, the two versions seem so similar that the cynic in me suggests that the 1978 revisions were published simply to allow an extension on the copyright--copyright terms at the time were much more limited and the one on Body Snatchers had nearly run out.)

In the two novel versions Miles, Becky, Jack, and Theodora are increasingly persecuted, then flee town only to find that they don't know where to go or what to do. So they return to town, where they are split up. Becky and Miles hide in a field just outside town--the field where, it turns out, a professor had discovered what he thought was most likely an alien plant, and then a few days later retracted his story. It is here where the aliens are growing their pods for distribution, and Miles and Becky make a desperate last stand, setting fire to the fields and smashing pods. The aliens recognize their defeat and the pods detach from the plants, fly up off the ground, and leave the planet. Miles and Becky reunite with Jack and Theodora and discover that the aliens have a curiously short lifespan; most of them die off within a few years.

The serial version is apparently much different: Robert Shelton in "Genre and Closure in the Seven Versions of Invasion of the Body Snatchers" mentions that the 1955 Dell paperback "is based on, and twice the length of, the serial" and that "in the 1954 serial, a posse of FBI agents armed with 'riot guns' and 'small, light, almost dainty-looking machine guns'" arrives on site, attracted by Miles' fire, and helps fend off the alien invasion.

What does it mean that the endings are so different? What point was Finney trying to make, or deciding not to make? Catherine Jurca, in "Of Satire and Sofas," calls the novel "an allegory of postwar suburbanisation," yet the article is too brief to offer much supporting evidence and it's left to the reader to remember the United States' postwar population boom and the move from the cities to the suburbs.

Michael Parkes, in "There Will Be No Survivors," takes the novel as a metaphor for a different kind of encroaching conformity, and the pods as representing a different threat to identity: the introduction of television into American culture. Parkes notes that "between 1948 and 1955, television was installed in nearly two-thirds of the nation's homes and became the mythic and ideological unifier of the fragmented post-war family" and served "as a sign of suburban achievement," yet one that moved the family away from the hearth and conversation to the television and silent viewing. Parkes notes the effect of television on bars and cafes, as well, and its corollary to the cafe scene in the novel when Miles and Becky go to the Sky Terrace in the Siegel film to find few customers and no live music, but instead a jukebox: "the artistry and individuality of the original band has been 'snatched' and replaced by an inferior technological substitute." In this reading, Parkes considers the story's message somewhat ironic, calling it "an anti-media discourse which in itself is contradictory, as the film [and book] itself exists within the media."

This interpretation of the book as an anti-media, Luddite response to technological innovation is interesting; yet by far the most common reading of the story is as a metaphor for the political climate in the United States during the Cold War--whether as one about McCarthyism or as one about the Red Scare. More on that, and on Finney's and Siegel's reactions to it, next post.

body snatchers mix, part 3

Some more songs tangentially related to the Body Snatchers stories, and more about the stories (with spoilers) below that:

Jimmy Bo Horne -- Get Happy

There's something here that reminds me of much of George McCrae's work, probably in the simple composition and the repetition, but also in the reliance on a sweet hook and an energetic horn section in a poppy R&B track with high-flying vocals. Another happy song, appropriately enough.

[The Legendary Henry Stone Presents: Jimmy Bo Horne @ emusic or @ amazon]

Shirley Bassey -- Hey Big Spender (Wild Oscar mix)

Bassey likes to make these big brassy music numbers that go well with Bond films (Goldfinger, Moonraker, Diamonds are Forever) and that get a deft parody in The Life of Brian ("He had arms ... and legs ... and hands ... and feet / This boy whose name was Brian"). The remix here decides that brassy isn't brassy enough, and so kicks it up a notch: adding breakneck percussion, muted guitar, vocal effects, and tempo changes.

[Shirley Bassey - The Greatest Hits]

J.J. Cale -- Call the Doctor

Countrified blues-rock, subdued delivery, plodding bass, sour horns, and electric guitar swelling into a stoned melancholy solo. The description sounds horrible but Cale pulls it off somehow.

[Naturally]

Eddie Floyd -- Bring It on Home To Me

Easy-going R&B, not pining, not pleading, not arguing a case so much as pointing out what a good time you could be having--hoping you'll come to your senses and come join in.

[Eddie Floyd - Chronicle: Greatest Hits]

Lou Rawls -- Bring It on Home

Nevermind the showboating at the beginning; give the song a minute (actually, 45 seconds). Let the bass come in and the funk get dropped; let Lou gather his evidence and practice his line of argument. It's a smooth-talking dapper performance, pitch-perfect and with just enough edge on it to let you know he's serious, but not so serious as to keep the jurors from clapping.

[Anthology]

Jack Finney has published at least three different versions of Body Snatchers: first as serialized in Collier's in November and December 1954, then as a book in 1955 (expanded and given a different climax) and then with further edits in 1978 to coincide with Philip Kaufman's second film version of the story.

The three have strong similarities, as could be expected. The text versions take place in Santa Mira, a small town outside San Francisco, and feature a doctor named Miles Bennell, a former flame named Becky Driscoll, a psychologist friend named Mannie Kaufman, a writer friend named Jack Belicec, and his wife Theodora. At the start of the story, Becky approaches Miles and tells him of her cousin Wilma who's become convinced that her Uncle Ira is not actually Uncle Ira; when they visit Wilma, she explains that her aunt hasn't noticed because she is also not her aunt. From there the details accrue suggesting that the humans are being besieged by aliens intent on replacing them, and the small group of humans decide to fight.

Along the way Becky and Miles, both divorced, find themselves increasingly attracted to each other. Becky has divorced recently and Miles five years earlier, yet Miles continues to be bothered by his divorce, taking it as a sign of some shameful defeat. There are scattered mentions throughout the novel, most of them wry, and others which seem either self-deluding or callous and sexist:

I'd seen Becky at least every other night all the past week, but not because there was any romance building up between us. It was just better than hanging around the pool hall, playing solitaire, or collecting stamps. She was a pleasant, comfortable way of spending some evenings, nothing more, and that suited me fine.Then there's this more telling passage as Miles is shaving:

--Body Snatchers, '55, p. 24

'You handsome bastard,' I said to my face. 'You can marry them, all right; you just can't stay married, that's your trouble. You are weak. Emotionally unstable. Basically insecure. A latent thumb-sucker. A cesspool of immaturity, unfit for adult responsibility." ... I cut it out, and finished shaving with the uncomfortable feeling that for all I knew it wasn't funny but true, that having failed with one woman, I was getting too involved with another, and that for my sake and hers, she should be anywhere but here under my roof.Both the paperback versions share Miles' self-doubt following his divorce, his penchant for prescribing sedatives, his passive wait-and-see attitude in the face of an obviously mounting crisis, and the curious marker of the body-snatched: an indifference to neighborhood upkeep. A visiting salesman complains that it's hard to get into and out of the town; coffee is hard to come by and tastes bad when a restaurant has it; and Miles notes that his Coca-Cola is warm. And outside the restaurant, on a littered street:

--Body Snatchers, '55, p.76

"Miles," she said in a cautious, lowered tone, "am I imagining it, or does this street look--dead?"Of the three versions, the Collier's version is probably the hardest to find: so far as I know it was never collected and published separately without changes, and it doesn't seem to be available in various academic databases, so finding it most likely requires access to the original magazines. I haven't read this version but I have the other two, and they're fairly similar. One of the more striking differences between the two novels happens early on when Miles mentions his car: "I drive a '52 Ford convertible, one of those fancy green ones, because I don't know of any law absolutely requiring a doctor to drive a small black coupé." (Finney '55, p. 13)

I shook my head. "No. In seven blocks we haven't passed a single house with as much as the trim being repainted; not a roof, porch, or even a cracked window being repaired; not a tree, shrub, or a blade of grass being planted, or even trimmed. Nothing's happening, Becky, nobody's doing anything. And they haven't for days, maybe weeks."

--Body Snatchers '55, p. 108

So early on Miles seems like a big spender, maybe a bit arrogant, maybe living a lavish lifestyle, with no time for Becky. In the 1978 version the passage is changed: "I drive a 1973 Mercedes two-seater, a nice fire-engine red job, bought used, to maintain the popular illusion that all doctors are rich." (Finney '78, p. 13)

Yet most of the differences between the two versions are subtle, perhaps inconsequential--instead of golf and swimming, Miles plays tennis, things like that. (In fact, the two versions seem so similar that the cynic in me suggests that the 1978 revisions were published simply to allow an extension on the copyright--copyright terms at the time were much more limited and the one on Body Snatchers had nearly run out.)

In the two novel versions Miles, Becky, Jack, and Theodora are increasingly persecuted, then flee town only to find that they don't know where to go or what to do. So they return to town, where they are split up. Becky and Miles hide in a field just outside town--the field where, it turns out, a professor had discovered what he thought was most likely an alien plant, and then a few days later retracted his story. It is here where the aliens are growing their pods for distribution, and Miles and Becky make a desperate last stand, setting fire to the fields and smashing pods. The aliens recognize their defeat and the pods detach from the plants, fly up off the ground, and leave the planet. Miles and Becky reunite with Jack and Theodora and discover that the aliens have a curiously short lifespan; most of them die off within a few years.

The serial version is apparently much different: Robert Shelton in "Genre and Closure in the Seven Versions of Invasion of the Body Snatchers" mentions that the 1955 Dell paperback "is based on, and twice the length of, the serial" and that "in the 1954 serial, a posse of FBI agents armed with 'riot guns' and 'small, light, almost dainty-looking machine guns'" arrives on site, attracted by Miles' fire, and helps fend off the alien invasion.

What does it mean that the endings are so different? What point was Finney trying to make, or deciding not to make? Catherine Jurca, in "Of Satire and Sofas," calls the novel "an allegory of postwar suburbanisation," yet the article is too brief to offer much supporting evidence and it's left to the reader to remember the United States' postwar population boom and the move from the cities to the suburbs.

Michael Parkes, in "There Will Be No Survivors," takes the novel as a metaphor for a different kind of encroaching conformity, and the pods as representing a different threat to identity: the introduction of television into American culture. Parkes notes that "between 1948 and 1955, television was installed in nearly two-thirds of the nation's homes and became the mythic and ideological unifier of the fragmented post-war family" and served "as a sign of suburban achievement," yet one that moved the family away from the hearth and conversation to the television and silent viewing. Parkes notes the effect of television on bars and cafes, as well, and its corollary to the cafe scene in the novel when Miles and Becky go to the Sky Terrace in the Siegel film to find few customers and no live music, but instead a jukebox: "the artistry and individuality of the original band has been 'snatched' and replaced by an inferior technological substitute." In this reading, Parkes considers the story's message somewhat ironic, calling it "an anti-media discourse which in itself is contradictory, as the film [and book] itself exists within the media."

This interpretation of the book as an anti-media, Luddite response to technological innovation is interesting; yet by far the most common reading of the story is as a metaphor for the political climate in the United States during the Cold War--whether as one about McCarthyism or as one about the Red Scare. More on that, and on Finney's and Siegel's reactions to it, next post.

Labels: about fiction, body snatchers, country blues, horror, RnB, vocal