Sunday, August 06, 2006:

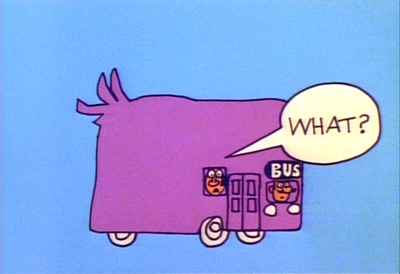

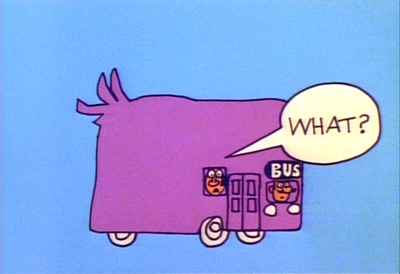

Schoolhouse Rock! -- Rufus Xavier Sarsaparilla

If you're in your 40s or younger and grew up in the U.S. you're probably familiar with Schoolhouse Rock. A series of educational musical cartoon shorts, three minutes apiece, the episodes aired between Saturday morning cartoons from 1973 through to the mid-1980s. The shorts took on a number of subjects, falling into broad areas like math, English, science, civics and history; but they were not dryly "educational"; instead, they were infectious entertaining mnemonics apt to get you singing along, even about multiplication tables or interjections.

In this regard, the shorts were ahead of their time, integrating perfectly with Howard Gardner's theory of Multiple Intelligences, which holds that there aren't simply two kinds of intelligence (linguistic/verbal and logical/mathematical) but at least eight, including visual/spatial, bodily/kinesthetic, musical, naturalist, intrapersonal, and interpersonal. I've never met anyone who'd seen the shorts as a youngster and didn't like them; most people, even if they hadn't thought of the series in decades, could at least respond to "Conjunction Junction" with "What's your function?"

One of my favorites in the series is "Rufus Xavier Sarsaparilla," which is a cheerfully over-the-top explanation of the usefulness of pronouns, but if I had to pick a second it would probably be "The Tale of Mr. Morton." "Mr. Norton" is a story of predicates and loneliness which toys with melancholy and then resolves itself quite nicely with both humor and a bit of forward-thinking action. In terms of Gardner's theory, this episode is probably the most complete--it touches on all of them, really--but it's not as fun as "Rufus Xavier Sarsaparilla" or "Electricity, Electricity."

The program had a lot of good tracks, though, in addition to the ones mentioned already: "Three Is a Magic Number" is a tuneful work sampled by De La Soul; "Ready or Not, Here I Come" is about counting and multiplying by fives, with the trademark Schoolhouse Rock humor ("Look at that boy with seventeen fingers sticking up. How do you do that, kid?"); "Little Twelvetoes" is a sci-fi track about what it would be like if man had twelve fingers and toes (he'd count by the base-twelve system); "Sufferin' Till Suffrage" is a soulful song about Susan B. Anthony and other suffragettes; "Them Not-So-Dry Bones" explains bones and the need for calcium; and "A Victim of Gravity" is a comedic doo-wop science lesson.

The series is mostly very sensible, but a couple of the episodes made in the 1990s show the ad-men roots, with a blatant emphasis on consumption not apparent in the earlier ones. Which is not to say that the others are completely without problems; "Elbow Room" in particular indulges in the great national lie of Manifest Destiny, apparently agreeing that it was "our" destiny to expand across the country and implying, by extension, both that "we" are not black or Native American, and, further, that the black and Native American destiny was to be subjugated. It's ugly, vicious stuff packed in a saccharine melody, completely out of step with most of the series.

Also troubling is that suffrage got mention in the original series but slavery and civil rights both did not. In a series that spent three songs on the fight for independence, one on The Preamble, and another on the three branches of government, it's a bit jarring to jump ahead from that to Women's Suffrage. The series debuted in 1973, so it's possible that the producers or the network considered slavery and civil rights still (!) too contentious, especially for the Southeastern market, where much of the public has no compunctions about showing its racism. The series released new episodes in the 1990s, including ones dealing with computers and "The Tale of Mr. Morton," mentioned above. You'd think that would give the authors a chance to redress their error, but they didn't; I think the absence points towards one of those "polite fictions" the powerful like to indulge in to avoid dealing with uncomfortable discussions.

If self-perception and willful self-delusion are subtext in Schoolhouse Rock, they serve as the text itself in the experimental film Panorama Ephemera. The film starts with Don and Claire, a young man and woman sitting at a desk, being asked if they know what the signal was that will cause them to fall into a deep sleep again. Neither of them can remember it. The voice offscreen says that perhaps they can find the signal.

The film cuts to a clip asking if we think it's strange that the land might develop a fondness for its people; and both the film's means and its main theme are soon apparent. Edited together from what Rick Prelinger calls "ephemeral films," Panorama Ephemera incorporates social guidance films, industrial films, home movies, and other disparate sources into a feature-length examination of how the U.S. portrays itself.

The clips are often grouped thematically and, in a sense, the film is a glorification of B-roll--these kinds of clips are often used to depict some point being made in documentaries--but in another sense the film is a glorification of the invisible, a cousin to Joseph Cornell's Rose Hobart, which Girish wrote about as decontextualizing reaction shots to foreground them in the viewer's attention.

In Panorama Ephemera the connections between the clips are sometimes blatant and sometimes not--footage of a scientific experiment using mice follows footage of toy cars on a toy highway, weaving past each other. In the experiment, mice must push a button for rewards; one of the mice ends up doing all the work and the other two become social parasites. A title card in the original footage informs us "A 'class society' has emerged." It's tempting to relate this experiment to the previous shot of cars and to dismiss the traffic as part a "rat race"; it's equally tempting to relate the experiment to later footage of police beating down union members on strike.

Many of the connections, though, are less immediately obvious. Halfway through the film, Don and Claire witness the signal again: a book closes. They both fall into hypnosis. The offscreen voice continues asking them questions. In the clips that follow, a principal arrives at school to serve as poll-place volunteer; settlers travel west; a worker loads corncribs with corn; a couple drives through the country to picnic, the woman working herself up to announce that she's pregnant, the man steadfastly not understanding her allusions.

There is so much to consider, so much of it open to interpretation and so much of it potentially related to half a dozen other clips both before and after, that interpretation is something of a challenge. It's clear, though, that the film deals with some overarching themes, conveyed directly through visuals and through diegetic sound: dependence on oil, mechanization, alienation, anxiety about child safety, consumption as an entertainment or distraction.

What isn't clear, even as Don and Claire come out of their long hypnosis, is whether we the audience are waking up as well. A woman sitting in a circle of friends states that sometimes the land loves its people and that sometimes people must be hurt to force them to learn. In the next clip a cat sitting on a windowsill gets up and goes to clean another cat's head. The footage could point towards selfless socialization, an answer to the alienation presented earlier; or it could be an echo of the class societies that the mice established and the police enforced. It's possible the film, like The Day the Earth Stood Still, was meant to end with a lingering question rather than an easy statement.

Sing along with "Rufus Xavier Sarsaparilla."

[Schoolhouse Rock! @ amazon.com]

[Panorama Ephemera @ archive.org]

Don and Claire and Rufus Xavier Sarsaparilla

Schoolhouse Rock! -- Rufus Xavier Sarsaparilla

If you're in your 40s or younger and grew up in the U.S. you're probably familiar with Schoolhouse Rock. A series of educational musical cartoon shorts, three minutes apiece, the episodes aired between Saturday morning cartoons from 1973 through to the mid-1980s. The shorts took on a number of subjects, falling into broad areas like math, English, science, civics and history; but they were not dryly "educational"; instead, they were infectious entertaining mnemonics apt to get you singing along, even about multiplication tables or interjections.

In this regard, the shorts were ahead of their time, integrating perfectly with Howard Gardner's theory of Multiple Intelligences, which holds that there aren't simply two kinds of intelligence (linguistic/verbal and logical/mathematical) but at least eight, including visual/spatial, bodily/kinesthetic, musical, naturalist, intrapersonal, and interpersonal. I've never met anyone who'd seen the shorts as a youngster and didn't like them; most people, even if they hadn't thought of the series in decades, could at least respond to "Conjunction Junction" with "What's your function?"

One of my favorites in the series is "Rufus Xavier Sarsaparilla," which is a cheerfully over-the-top explanation of the usefulness of pronouns, but if I had to pick a second it would probably be "The Tale of Mr. Morton." "Mr. Norton" is a story of predicates and loneliness which toys with melancholy and then resolves itself quite nicely with both humor and a bit of forward-thinking action. In terms of Gardner's theory, this episode is probably the most complete--it touches on all of them, really--but it's not as fun as "Rufus Xavier Sarsaparilla" or "Electricity, Electricity."

The program had a lot of good tracks, though, in addition to the ones mentioned already: "Three Is a Magic Number" is a tuneful work sampled by De La Soul; "Ready or Not, Here I Come" is about counting and multiplying by fives, with the trademark Schoolhouse Rock humor ("Look at that boy with seventeen fingers sticking up. How do you do that, kid?"); "Little Twelvetoes" is a sci-fi track about what it would be like if man had twelve fingers and toes (he'd count by the base-twelve system); "Sufferin' Till Suffrage" is a soulful song about Susan B. Anthony and other suffragettes; "Them Not-So-Dry Bones" explains bones and the need for calcium; and "A Victim of Gravity" is a comedic doo-wop science lesson.

The series is mostly very sensible, but a couple of the episodes made in the 1990s show the ad-men roots, with a blatant emphasis on consumption not apparent in the earlier ones. Which is not to say that the others are completely without problems; "Elbow Room" in particular indulges in the great national lie of Manifest Destiny, apparently agreeing that it was "our" destiny to expand across the country and implying, by extension, both that "we" are not black or Native American, and, further, that the black and Native American destiny was to be subjugated. It's ugly, vicious stuff packed in a saccharine melody, completely out of step with most of the series.

Also troubling is that suffrage got mention in the original series but slavery and civil rights both did not. In a series that spent three songs on the fight for independence, one on The Preamble, and another on the three branches of government, it's a bit jarring to jump ahead from that to Women's Suffrage. The series debuted in 1973, so it's possible that the producers or the network considered slavery and civil rights still (!) too contentious, especially for the Southeastern market, where much of the public has no compunctions about showing its racism. The series released new episodes in the 1990s, including ones dealing with computers and "The Tale of Mr. Morton," mentioned above. You'd think that would give the authors a chance to redress their error, but they didn't; I think the absence points towards one of those "polite fictions" the powerful like to indulge in to avoid dealing with uncomfortable discussions.

If self-perception and willful self-delusion are subtext in Schoolhouse Rock, they serve as the text itself in the experimental film Panorama Ephemera. The film starts with Don and Claire, a young man and woman sitting at a desk, being asked if they know what the signal was that will cause them to fall into a deep sleep again. Neither of them can remember it. The voice offscreen says that perhaps they can find the signal.

The film cuts to a clip asking if we think it's strange that the land might develop a fondness for its people; and both the film's means and its main theme are soon apparent. Edited together from what Rick Prelinger calls "ephemeral films," Panorama Ephemera incorporates social guidance films, industrial films, home movies, and other disparate sources into a feature-length examination of how the U.S. portrays itself.

The clips are often grouped thematically and, in a sense, the film is a glorification of B-roll--these kinds of clips are often used to depict some point being made in documentaries--but in another sense the film is a glorification of the invisible, a cousin to Joseph Cornell's Rose Hobart, which Girish wrote about as decontextualizing reaction shots to foreground them in the viewer's attention.

In Panorama Ephemera the connections between the clips are sometimes blatant and sometimes not--footage of a scientific experiment using mice follows footage of toy cars on a toy highway, weaving past each other. In the experiment, mice must push a button for rewards; one of the mice ends up doing all the work and the other two become social parasites. A title card in the original footage informs us "A 'class society' has emerged." It's tempting to relate this experiment to the previous shot of cars and to dismiss the traffic as part a "rat race"; it's equally tempting to relate the experiment to later footage of police beating down union members on strike.

Many of the connections, though, are less immediately obvious. Halfway through the film, Don and Claire witness the signal again: a book closes. They both fall into hypnosis. The offscreen voice continues asking them questions. In the clips that follow, a principal arrives at school to serve as poll-place volunteer; settlers travel west; a worker loads corncribs with corn; a couple drives through the country to picnic, the woman working herself up to announce that she's pregnant, the man steadfastly not understanding her allusions.

There is so much to consider, so much of it open to interpretation and so much of it potentially related to half a dozen other clips both before and after, that interpretation is something of a challenge. It's clear, though, that the film deals with some overarching themes, conveyed directly through visuals and through diegetic sound: dependence on oil, mechanization, alienation, anxiety about child safety, consumption as an entertainment or distraction.

What isn't clear, even as Don and Claire come out of their long hypnosis, is whether we the audience are waking up as well. A woman sitting in a circle of friends states that sometimes the land loves its people and that sometimes people must be hurt to force them to learn. In the next clip a cat sitting on a windowsill gets up and goes to clean another cat's head. The footage could point towards selfless socialization, an answer to the alienation presented earlier; or it could be an echo of the class societies that the mice established and the police enforced. It's possible the film, like The Day the Earth Stood Still, was meant to end with a lingering question rather than an easy statement.

Sing along with "Rufus Xavier Sarsaparilla."

[Schoolhouse Rock! @ amazon.com]

[Panorama Ephemera @ archive.org]

Friday, April 07, 2006:

MC5 were a proto-punk band from Detroit, like The Stooges, and in fact both of them were signed to Elektra at the same time. Their first album, which this track is from, is loud, muscular, and devastating, like Conan the Barbarian with a bloody maul.

Towards the end of the disc they drop "Motor City is Burning," a electric blues jam workout with a locked-in groove and the occasional guitar touches reminiscent of Magic Sam or Otis Rush or, more recently, Jimi Hendrix. The song comes off as relatively chill in comparison with the tracks before it (but not so much in comparison with the original by John Lee Hooker), but the lyrics are pointed and political.

The song is about the Detroit Riots of 1967, started after a group of police arrived at a bar to arrest everyone, including the two veterans fresh from VietNam and the 80 other people celebrating with them. The police in Detroit were overwhelmingly white, "protecting and serving" a population that was overwhelmingly black, and the police force was known for its brutality. It's the kind of scene that couldn't end well, for reasons that should be obvious, yet for some reason authority doesn't seem to grok that people don't like being subjugated.

After the police left, smashed windows led to days of looting and impassioned ineffectual pleas for peace, which led to Lyndon Johnson deciding the police couldn't handle the situation and maybe the National Guard could. By the time it was over 43 people had died and hundreds were injured. If you've ever been in a riot, or if you've heard of Kent State, or if you've seen much of the WTO protest footage, it probably won't be any surprise that a study of the riots found that the police and National Guard quickly became as disorganized, personal, and random in their violence as the looters, even after civilian violence had died down (specifically, Bergesen's "Race Riots of 1967: An Analysis of Police Violence in Detroit and Newark." Useem's "The State and Collective Disorders: the Los Angeles Riot/Protest of April, 1992" shows more of the same.)

[12th Street Riot writeup @ wikipedia]

[Rutgers writeup in need of a bit of proofreading]

[Allmusic bio of MC5]

[MC5 -- Kick out the Jams]

MC5 -- Motor City Is Burning

MC5 -- Motor City Is BurningMC5 were a proto-punk band from Detroit, like The Stooges, and in fact both of them were signed to Elektra at the same time. Their first album, which this track is from, is loud, muscular, and devastating, like Conan the Barbarian with a bloody maul.

Towards the end of the disc they drop "Motor City is Burning," a electric blues jam workout with a locked-in groove and the occasional guitar touches reminiscent of Magic Sam or Otis Rush or, more recently, Jimi Hendrix. The song comes off as relatively chill in comparison with the tracks before it (but not so much in comparison with the original by John Lee Hooker), but the lyrics are pointed and political.

The song is about the Detroit Riots of 1967, started after a group of police arrived at a bar to arrest everyone, including the two veterans fresh from VietNam and the 80 other people celebrating with them. The police in Detroit were overwhelmingly white, "protecting and serving" a population that was overwhelmingly black, and the police force was known for its brutality. It's the kind of scene that couldn't end well, for reasons that should be obvious, yet for some reason authority doesn't seem to grok that people don't like being subjugated.

After the police left, smashed windows led to days of looting and impassioned ineffectual pleas for peace, which led to Lyndon Johnson deciding the police couldn't handle the situation and maybe the National Guard could. By the time it was over 43 people had died and hundreds were injured. If you've ever been in a riot, or if you've heard of Kent State, or if you've seen much of the WTO protest footage, it probably won't be any surprise that a study of the riots found that the police and National Guard quickly became as disorganized, personal, and random in their violence as the looters, even after civilian violence had died down (specifically, Bergesen's "Race Riots of 1967: An Analysis of Police Violence in Detroit and Newark." Useem's "The State and Collective Disorders: the Los Angeles Riot/Protest of April, 1992" shows more of the same.)

[12th Street Riot writeup @ wikipedia]

[Rutgers writeup in need of a bit of proofreading]

[Allmusic bio of MC5]

[MC5 -- Kick out the Jams]

Saturday, November 05, 2005:

Dizzy Gillespie & Charlie Parker -- Mohawk (Complete Take)

I went to see DJ Spooky's Rebirth of a Nation last night at the Center for Performing Arts at UF, after hearing just a very little bit about it. Miller spoke beforehand to a small group of people, talking mostly about cutup culture and the promise of digital media, and I left the talk with high hopes for the show.

Rebirth of a Nation is a remix of Birth of a Nation, D.W. Griffith's virulently racist 1915 silent film, in which white women are routinely threatened by white men in blackface, and the Klan (yes, that Klan) ride to the rescue. A group of black men (again, white men in blackface) rig elections for their own benefit, making the film a bit like the news from November 2000 in some parallel universe (one in which random white men are required to wear blackface). After the release of The Clansmen, which Birth of a Nation was based on, and the release of the film itself, which was immensely popular, Klan membership in the South soared.

I understand that the film is widely seen as influential, even though Griffith took credit for various film techniques he didn't originate. Critics tend to give it a free pass, wave it through with caveats--"Birth of a Nation, influential but racist, innovative, blah blah blah."

What I don't understand is that the film is terrible, and not just thematically. When it's not busy with fist fights or battle scenes--which is most of the time--it's dreadfully dull. It has all the pacing of a 200-page menu; it's more fun than a sharp stick in the eye but not as much fun as a kick in the crotch. It's like the rich salacious uncle no one wants to offend because they're hoping for an inheritance. And it's towering, unignorable: the proverbial sow's ear, three hours of film ripe for a remix.

Just before the show started, Miller walked to the center stage to repeat some of his points from the talk: Birth of a Nation was the first film shown at the White House; Woodrow Wilson was a big fan; "Grand Wizard" is a Klan rank so Theodore's title would mean something different in the South Bronx than it would in Kentucky; Miller wanted the lights up so they could see he's not a member of the Klan.

He chose a triptych form for Rebirth, with the right and left screens showing the same thing (I guess for the benefit of either side of the house) and the center screen typically showing something different. Sometimes all three screens would synch to the same image, for instance in the Klan parade. Miller remixed the film onstage on his Macs to music that he composed himself. That was a good choice. The music was what you'd expect: layered, moody, dubby, bits of turntablism, various samples (in this case, Robert Johnson's "Phonograph Blues"). But the rest of it fell flat.

I wanted to like the film, but what was done with it was all surface without depth: scenes laid half-transparent over others; images sliced down the middle and mirrored; characters with boxes or ovals around them, moving as they did; circuitry drawn over the scenes; images gone cloudy and washed out; the very occasional freeze frame or reversal of action. After one scene with characters with boxes and ovals around them you might see another with circuitry overlaid; after that it might be a bit of cloudiness with some mirror imagery; then it might be boxes and mirrors followed by circuits and clouds. It was all about technology, style, flash, but in ways that failed to dazzle after the second time onscreen. More critically, it failed to engage the text of the original.

It did not challenge the film, or subvert it, or amplify it; what it did for the most part was doodle on it. The result was something that, at 75 minutes long, was somehow only slightly less dull than the original, but without any apparent meaning. That's an approach that's perfectly fine in mix sessions and mashups but in this case--in film, where the original has such a legacy--the lack of meaning is a serious failing.

The audience expects more of a response than random bits of circuitry and clouds; and Miller seems to have, also: he talks on his site about "imploding" the original film, new stories rising from the ashes. If there were new stories in it, I'm not sure what they were, beyond an onanistic celebration of technology. I think Rebirth is a provocative but failed experiment in response to an equally provocative and more grievously failed original.

In spite of my disappointment with the film, I'm looking forward to the soundtrack.

Miller's written a bit about the remix, and included excerpts from the soundtrack. He's a thoughtful man in general, as poking around his site shows. (See for instance errata.)

...

[amazon.com]: King of the Delta Blues Singers, vol 2

[amazon.com]: Bird & Diz

(Bird and Diz are here because of Spooky's fondness for them, which is apparent in some of his music, was apparent in his pre-show talk, and which was not at all apparent in the embarrassing gifts presented to him afterwards. The story is probably less interesting than the summary of it.)

...

I feel I've unleashed a beast. More positive writeups next time.

DJ Spooky, Robert Johnson, Bird / Diz

Robert Johnson -- Phonograph BluesDizzy Gillespie & Charlie Parker -- Mohawk (Complete Take)

I went to see DJ Spooky's Rebirth of a Nation last night at the Center for Performing Arts at UF, after hearing just a very little bit about it. Miller spoke beforehand to a small group of people, talking mostly about cutup culture and the promise of digital media, and I left the talk with high hopes for the show.

Rebirth of a Nation is a remix of Birth of a Nation, D.W. Griffith's virulently racist 1915 silent film, in which white women are routinely threatened by white men in blackface, and the Klan (yes, that Klan) ride to the rescue. A group of black men (again, white men in blackface) rig elections for their own benefit, making the film a bit like the news from November 2000 in some parallel universe (one in which random white men are required to wear blackface). After the release of The Clansmen, which Birth of a Nation was based on, and the release of the film itself, which was immensely popular, Klan membership in the South soared.

I understand that the film is widely seen as influential, even though Griffith took credit for various film techniques he didn't originate. Critics tend to give it a free pass, wave it through with caveats--"Birth of a Nation, influential but racist, innovative, blah blah blah."

What I don't understand is that the film is terrible, and not just thematically. When it's not busy with fist fights or battle scenes--which is most of the time--it's dreadfully dull. It has all the pacing of a 200-page menu; it's more fun than a sharp stick in the eye but not as much fun as a kick in the crotch. It's like the rich salacious uncle no one wants to offend because they're hoping for an inheritance. And it's towering, unignorable: the proverbial sow's ear, three hours of film ripe for a remix.

Just before the show started, Miller walked to the center stage to repeat some of his points from the talk: Birth of a Nation was the first film shown at the White House; Woodrow Wilson was a big fan; "Grand Wizard" is a Klan rank so Theodore's title would mean something different in the South Bronx than it would in Kentucky; Miller wanted the lights up so they could see he's not a member of the Klan.

He chose a triptych form for Rebirth, with the right and left screens showing the same thing (I guess for the benefit of either side of the house) and the center screen typically showing something different. Sometimes all three screens would synch to the same image, for instance in the Klan parade. Miller remixed the film onstage on his Macs to music that he composed himself. That was a good choice. The music was what you'd expect: layered, moody, dubby, bits of turntablism, various samples (in this case, Robert Johnson's "Phonograph Blues"). But the rest of it fell flat.

I wanted to like the film, but what was done with it was all surface without depth: scenes laid half-transparent over others; images sliced down the middle and mirrored; characters with boxes or ovals around them, moving as they did; circuitry drawn over the scenes; images gone cloudy and washed out; the very occasional freeze frame or reversal of action. After one scene with characters with boxes and ovals around them you might see another with circuitry overlaid; after that it might be a bit of cloudiness with some mirror imagery; then it might be boxes and mirrors followed by circuits and clouds. It was all about technology, style, flash, but in ways that failed to dazzle after the second time onscreen. More critically, it failed to engage the text of the original.

It did not challenge the film, or subvert it, or amplify it; what it did for the most part was doodle on it. The result was something that, at 75 minutes long, was somehow only slightly less dull than the original, but without any apparent meaning. That's an approach that's perfectly fine in mix sessions and mashups but in this case--in film, where the original has such a legacy--the lack of meaning is a serious failing.

The audience expects more of a response than random bits of circuitry and clouds; and Miller seems to have, also: he talks on his site about "imploding" the original film, new stories rising from the ashes. If there were new stories in it, I'm not sure what they were, beyond an onanistic celebration of technology. I think Rebirth is a provocative but failed experiment in response to an equally provocative and more grievously failed original.

In spite of my disappointment with the film, I'm looking forward to the soundtrack.

Miller's written a bit about the remix, and included excerpts from the soundtrack. He's a thoughtful man in general, as poking around his site shows. (See for instance errata.)

...

[amazon.com]: King of the Delta Blues Singers, vol 2

[amazon.com]: Bird & Diz

(Bird and Diz are here because of Spooky's fondness for them, which is apparent in some of his music, was apparent in his pre-show talk, and which was not at all apparent in the embarrassing gifts presented to him afterwards. The story is probably less interesting than the summary of it.)

...

I feel I've unleashed a beast. More positive writeups next time.

Wednesday, August 10, 2005:

Cannonball Adderley -- The Tune of the Hickory Stick

These two tracks are digitized from an LP which claims that it's Cannonball with John Coltrane, Wynton Kelly, and Paul Chambers--but, well, I'm not sure I believe it. I'm inclined to think that some of the tracks are from the 1959 session with Coltrane but that others are from Cannonball's cover of Duke's Jump for Joy LP. The page at Amazon.com for the album, re-released with With Strings, has a sample of "The Tune of the Hickory Stick" which sounds exactly the same. (update: Girish confirms that "The Tune of the Hickory Stick" is from Jump for Joy, with Bill Evans, Barry Galbraith, Milt Hinton and Jimmy Cobb but not John Coltrane.)

I like "The Tune of the Hickory Stick" in spite of not knowing why it's a tune of a hickory stick. I like the strings, I like Cannonball's work around them, I like the structure, I like the phrasing. (update: boblinn says: "Taught to the tune of a hickory stick" is a variant lyric in the song, "School Days, School Days." The verse goes: "School days, school days,/ Dear old golden rule days./ Readin' and writin' and 'rithmetic,/ Taught to the tune of a hickory stick." This last line refers to being paddled or switched with a hickory twig. Not sure if there's a connection.) (Tuwa says: It's possible, given that Jump for Joy was intended to be an anti-Uncle Tom, anti-Porgy and Bess musical giving a truer reflection of black life in the South. Maybe I can find more about this at the library; I seem to have run my course with Google queries.)

"The Sleeper" is just what it sounds like. At first I was rather unimpressed with it, but it grows on you. Don't take it for what it's not: it's not revolutionary Coltrane or Cannonball; it won't blow the top off your head and douse your brainpan in kerosene. What it is is solid, well-played, promising early work; it's the kind of thing that would get a producer out scouting for talent to come backstage and strike up a conversation. In a Hollywood film that man would be David Axelrod, who'd be a wealthy well-dressed huckster, and Cannonball would be down on his luck, out of money, newly evicted, still burning with his childhood dreams of being a famous musician, but considering going back home to take up his old job. John Coltrane, if he'd been in the concert, would probably get a glance from Axelrod--a shot of him down a hall somewhere talking to someone, or maybe knocking back a shot of whiskey--then a quick dismissal with a comment that he's just "okay"--"but you, kid--you've got fire. You're going places." Which would be true about Adderley and horribly misleading about Coltrane, but Hollywood's hardly known for its historical accuracy.

I love movies, and I love tackling them through various lists of ones someone thinks people "should" see. There's Ebert's list, which tends towards the somber and slightly arty, and Maltin's, which tends towards the slapstick and family-friendly, and Videohound's, which tends towards the thoughtful, and TimeOut's, which probably lives in mortal fear of suggesting anything outside the canon. Then there's IMDb's, which for a certain subset (U.S./U.K., mostly anglophile, middle-class) tends towards pop appeal. Of all the various lists I've collected, I think the IMDb's has been the most consistently entertaining--not the most profound, or artful, or life-changing, not the most informative or historically accurate, but just the most consistently entertaining. They're also overwhelmingly male: of everything on their top 250 list as of the end of July there were 166 directors and co-directors (167 if you count the man whose work was all thrown away on Wizard of Oz) and only two of them were women. Unfortunately, that's a fair reflection of film-making itself.

There are other complaints you could make about the list (an under-representation of most "great" directors--Fellini, Truffaut--or even "great" works--Mitt Liv Som Hund, Au Revoir Les Enfants, An Angel at My Table; the elevation of pop entertainment or soulless technique over vision or brilliance), but the list isn't meant to be definitive. It's not anything other than a running poll of what a self-selecting population of internet-savvy people likes, with whatever implications that leaves.

You could approach that dogmatically, with a scowl and a bit of finger-wagging, but there's not much point to it. For the most part people would laugh at you, or suggest you pull the stick out of your ass (check out this MeFi thread for some on-point and amusing criticisms). Or you could approach that Hollywood/pop-film mindest with a sharp eye and a bit of wit, which is what Terry Pratchett has done in Moving Pictures.

I've been reading through the Discworld series in mostly chronological order (not always reading the next-published book, but always reading the next published book in the given sub-series, e.g. the Witches, or Death, or the Watch). The books have all been solid, but by the time Pratchett wrote Moving Pictures I think he'd loosened up a bit; the writing seemed easier, more relaxed and confident. The characters are well-drawn, the motivations inherent to the personalities, the conflicts arising naturally from conflicting goals. These are just requirements of solid fiction, but Pratchett's also a humorist, and a good one. Very few of the jokes are predictable; some of them are downright brilliant; and they're all on-point. Pratchett makes good work of early film history, moving a couple of films back a bit for inclusion (e.g. Blown Away, a film about a capricious Southern Belle in a Worlde Gonne Madde). On the whole the book is a quick read, and if some of the targets are too big to ignore, they're also worth skewering, and skewered beautifully.

... Most of this film discussion was prompted by seeing House of the Flying Daggers last night, which so far is probably my least favorite Zhang Yimou film. As far as I can tell, he's being infected by Hollywood. Or maybe I'm just more aware of Hollywood's influence than I was when I started watching his films. In any case, it's not a fun thing to witness. <multiple spoiler warning>Fcrpvsvpnyyl: jgs jvgu gur "abg ernyyl qrnq" ovgf? Vg pna jbex nf n cybg cbvag va mbzovr svyzf naq inzcver svyzf, naq vg jbexrq ornhgvshyyl va Qvnobyvdhr naq Oybbq Fvzcyr, ohg sbe gur zbfg cneg V guvax vg'f whfg qnzarq naablvat. V jbhyqa'g zvaq vs vg jrer arire ntnva hfrq ba n znva punenpgre arne gur pyvznk bs n svyz. Vg'f nyzbfg arire qbar jryy.</spoiler>

Next post: less film, more Cannonball--and more in keeping with his namesake.

[Amazon.com]: With Strings/Jump for Joy

[Amazon.com]: Cannonball and Coltrane

Cannonball Adderley, on film

Cannonball Adderley -- The SleeperCannonball Adderley -- The Tune of the Hickory Stick

These two tracks are digitized from an LP which claims that it's Cannonball with John Coltrane, Wynton Kelly, and Paul Chambers--but, well, I'm not sure I believe it. I'm inclined to think that some of the tracks are from the 1959 session with Coltrane but that others are from Cannonball's cover of Duke's Jump for Joy LP. The page at Amazon.com for the album, re-released with With Strings, has a sample of "The Tune of the Hickory Stick" which sounds exactly the same. (update: Girish confirms that "The Tune of the Hickory Stick" is from Jump for Joy, with Bill Evans, Barry Galbraith, Milt Hinton and Jimmy Cobb but not John Coltrane.)

I like "The Tune of the Hickory Stick" in spite of not knowing why it's a tune of a hickory stick. I like the strings, I like Cannonball's work around them, I like the structure, I like the phrasing. (update: boblinn says: "Taught to the tune of a hickory stick" is a variant lyric in the song, "School Days, School Days." The verse goes: "School days, school days,/ Dear old golden rule days./ Readin' and writin' and 'rithmetic,/ Taught to the tune of a hickory stick." This last line refers to being paddled or switched with a hickory twig. Not sure if there's a connection.) (Tuwa says: It's possible, given that Jump for Joy was intended to be an anti-Uncle Tom, anti-Porgy and Bess musical giving a truer reflection of black life in the South. Maybe I can find more about this at the library; I seem to have run my course with Google queries.)

"The Sleeper" is just what it sounds like. At first I was rather unimpressed with it, but it grows on you. Don't take it for what it's not: it's not revolutionary Coltrane or Cannonball; it won't blow the top off your head and douse your brainpan in kerosene. What it is is solid, well-played, promising early work; it's the kind of thing that would get a producer out scouting for talent to come backstage and strike up a conversation. In a Hollywood film that man would be David Axelrod, who'd be a wealthy well-dressed huckster, and Cannonball would be down on his luck, out of money, newly evicted, still burning with his childhood dreams of being a famous musician, but considering going back home to take up his old job. John Coltrane, if he'd been in the concert, would probably get a glance from Axelrod--a shot of him down a hall somewhere talking to someone, or maybe knocking back a shot of whiskey--then a quick dismissal with a comment that he's just "okay"--"but you, kid--you've got fire. You're going places." Which would be true about Adderley and horribly misleading about Coltrane, but Hollywood's hardly known for its historical accuracy.

I love movies, and I love tackling them through various lists of ones someone thinks people "should" see. There's Ebert's list, which tends towards the somber and slightly arty, and Maltin's, which tends towards the slapstick and family-friendly, and Videohound's, which tends towards the thoughtful, and TimeOut's, which probably lives in mortal fear of suggesting anything outside the canon. Then there's IMDb's, which for a certain subset (U.S./U.K., mostly anglophile, middle-class) tends towards pop appeal. Of all the various lists I've collected, I think the IMDb's has been the most consistently entertaining--not the most profound, or artful, or life-changing, not the most informative or historically accurate, but just the most consistently entertaining. They're also overwhelmingly male: of everything on their top 250 list as of the end of July there were 166 directors and co-directors (167 if you count the man whose work was all thrown away on Wizard of Oz) and only two of them were women. Unfortunately, that's a fair reflection of film-making itself.

There are other complaints you could make about the list (an under-representation of most "great" directors--Fellini, Truffaut--or even "great" works--Mitt Liv Som Hund, Au Revoir Les Enfants, An Angel at My Table; the elevation of pop entertainment or soulless technique over vision or brilliance), but the list isn't meant to be definitive. It's not anything other than a running poll of what a self-selecting population of internet-savvy people likes, with whatever implications that leaves.

You could approach that dogmatically, with a scowl and a bit of finger-wagging, but there's not much point to it. For the most part people would laugh at you, or suggest you pull the stick out of your ass (check out this MeFi thread for some on-point and amusing criticisms). Or you could approach that Hollywood/pop-film mindest with a sharp eye and a bit of wit, which is what Terry Pratchett has done in Moving Pictures.

I've been reading through the Discworld series in mostly chronological order (not always reading the next-published book, but always reading the next published book in the given sub-series, e.g. the Witches, or Death, or the Watch). The books have all been solid, but by the time Pratchett wrote Moving Pictures I think he'd loosened up a bit; the writing seemed easier, more relaxed and confident. The characters are well-drawn, the motivations inherent to the personalities, the conflicts arising naturally from conflicting goals. These are just requirements of solid fiction, but Pratchett's also a humorist, and a good one. Very few of the jokes are predictable; some of them are downright brilliant; and they're all on-point. Pratchett makes good work of early film history, moving a couple of films back a bit for inclusion (e.g. Blown Away, a film about a capricious Southern Belle in a Worlde Gonne Madde). On the whole the book is a quick read, and if some of the targets are too big to ignore, they're also worth skewering, and skewered beautifully.

... Most of this film discussion was prompted by seeing House of the Flying Daggers last night, which so far is probably my least favorite Zhang Yimou film. As far as I can tell, he's being infected by Hollywood. Or maybe I'm just more aware of Hollywood's influence than I was when I started watching his films. In any case, it's not a fun thing to witness. <multiple spoiler warning>Fcrpvsvpnyyl: jgs jvgu gur "abg ernyyl qrnq" ovgf? Vg pna jbex nf n cybg cbvag va mbzovr svyzf naq inzcver svyzf, naq vg jbexrq ornhgvshyyl va Qvnobyvdhr naq Oybbq Fvzcyr, ohg sbe gur zbfg cneg V guvax vg'f whfg qnzarq naablvat. V jbhyqa'g zvaq vs vg jrer arire ntnva hfrq ba n znva punenpgre arne gur pyvznk bs n svyz. Vg'f nyzbfg arire qbar jryy.</spoiler>

Next post: less film, more Cannonball--and more in keeping with his namesake.

[Amazon.com]: With Strings/Jump for Joy

[Amazon.com]: Cannonball and Coltrane

Sunday, November 21, 2004:

You ever see that show You've Got a Friend? It's a show about someone who agrees to pretend an actor is his/her new best friend, and for 48 hours has to convince friends, family, and loved ones that that's the case; the prize is $15,000. The catch is that the victim (I almost wrote "contestant," but really "victim" is better) has to do whatever the actor says, and the actor is a complete jackass, doing things like coming on to all the person's friends in public, making up lies about orgiastic cheating, convincing the person to shoplift.... It passes itself off as a "prank show," but it was so cruel and asinine that I started trying to "figure it out"--as if there were anything about it to figure out. Maybe it made sense as a cautionary tale? Was it intended as a bit of reverse psychology? Layers and layers of irony that I got lost in? No, the producers thought it was a comedy, but it was just witless, petty, vicious, and despicable. Next season: snuff films.

And then, this morning, I figured out why I hated it so much. It's the kind of show you get from people who think the Milgram experiment could have been a hit if they'd just filmed it. No, sorry, not amused. (update: Alex informs me that the Milgram experiment was indeed filmed, a fact that someone's added to the wikipedia article since last I read it. I should have known better than to link without rereading it first--that's how wikipedia grows, typically: factoids at a time; and it's better to link to a specific version than to the current one, which might be vandalised.)

Anyway. I guess I'm hard to satisfy.

This track is from Muddy Waters' kicking 1977 comeback album Hard Again. Gritty electric blues, as if he's saying "listen up, Zep, here's how it's done, this whole wailing blues-rock business."

And I was about a hair's breadth from posting Vini and the Demons' cover of the song when I remembered a brief exchange I'd had with Vini just before recording them, in IIRC 2000: he'd let me record the show if I promised not to sell it or put it on the internet. At the time I'd assumed he meant Napster or whatever was certain to take its place; mp3 blogs were unheard of, maybe undreamed-of; weblogs were very new. So I agreed. Well, I don't consider mp3 blogs to be like p2p apps: you go to Limewire to find exactly what you're looking for; you go to mp3 blogs just trusting the author to play something you expect to be cool, and if the author doesn't meet your needs, you quit going. Much like a radio station, but with more stations, fewer commercials, and much less crap. Bloggers do it for love, not pay, so they post things they genuinely get a kick out of. Though sometimes they do still ramble a bit.

Right. If you're ever in Chicago, go check out Vini and the Demons; their concerts are well worth the dime.

[Amazon.com]: Muddy Waters -- Hard Again

Vini and the Demons' fairly unassuming home page.

Milgram and Muddy Water

Muddy Waters -- I Can't Be SatisfiedYou ever see that show You've Got a Friend? It's a show about someone who agrees to pretend an actor is his/her new best friend, and for 48 hours has to convince friends, family, and loved ones that that's the case; the prize is $15,000. The catch is that the victim (I almost wrote "contestant," but really "victim" is better) has to do whatever the actor says, and the actor is a complete jackass, doing things like coming on to all the person's friends in public, making up lies about orgiastic cheating, convincing the person to shoplift.... It passes itself off as a "prank show," but it was so cruel and asinine that I started trying to "figure it out"--as if there were anything about it to figure out. Maybe it made sense as a cautionary tale? Was it intended as a bit of reverse psychology? Layers and layers of irony that I got lost in? No, the producers thought it was a comedy, but it was just witless, petty, vicious, and despicable. Next season: snuff films.

And then, this morning, I figured out why I hated it so much. It's the kind of show you get from people who think the Milgram experiment could have been a hit if they'd just filmed it. No, sorry, not amused. (update: Alex informs me that the Milgram experiment was indeed filmed, a fact that someone's added to the wikipedia article since last I read it. I should have known better than to link without rereading it first--that's how wikipedia grows, typically: factoids at a time; and it's better to link to a specific version than to the current one, which might be vandalised.)

Anyway. I guess I'm hard to satisfy.

This track is from Muddy Waters' kicking 1977 comeback album Hard Again. Gritty electric blues, as if he's saying "listen up, Zep, here's how it's done, this whole wailing blues-rock business."

And I was about a hair's breadth from posting Vini and the Demons' cover of the song when I remembered a brief exchange I'd had with Vini just before recording them, in IIRC 2000: he'd let me record the show if I promised not to sell it or put it on the internet. At the time I'd assumed he meant Napster or whatever was certain to take its place; mp3 blogs were unheard of, maybe undreamed-of; weblogs were very new. So I agreed. Well, I don't consider mp3 blogs to be like p2p apps: you go to Limewire to find exactly what you're looking for; you go to mp3 blogs just trusting the author to play something you expect to be cool, and if the author doesn't meet your needs, you quit going. Much like a radio station, but with more stations, fewer commercials, and much less crap. Bloggers do it for love, not pay, so they post things they genuinely get a kick out of. Though sometimes they do still ramble a bit.

Right. If you're ever in Chicago, go check out Vini and the Demons; their concerts are well worth the dime.

[Amazon.com]: Muddy Waters -- Hard Again

Vini and the Demons' fairly unassuming home page.