Sunday, August 06, 2006:

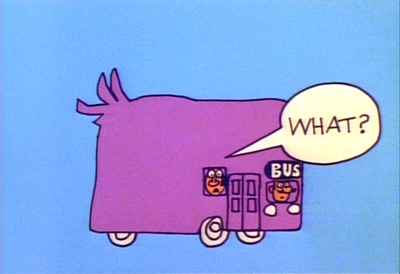

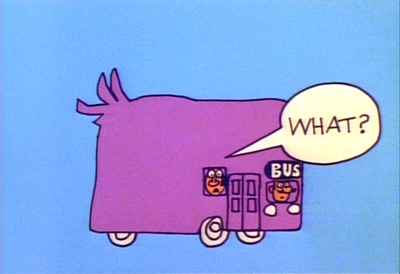

Schoolhouse Rock! -- Rufus Xavier Sarsaparilla

If you're in your 40s or younger and grew up in the U.S. you're probably familiar with Schoolhouse Rock. A series of educational musical cartoon shorts, three minutes apiece, the episodes aired between Saturday morning cartoons from 1973 through to the mid-1980s. The shorts took on a number of subjects, falling into broad areas like math, English, science, civics and history; but they were not dryly "educational"; instead, they were infectious entertaining mnemonics apt to get you singing along, even about multiplication tables or interjections.

In this regard, the shorts were ahead of their time, integrating perfectly with Howard Gardner's theory of Multiple Intelligences, which holds that there aren't simply two kinds of intelligence (linguistic/verbal and logical/mathematical) but at least eight, including visual/spatial, bodily/kinesthetic, musical, naturalist, intrapersonal, and interpersonal. I've never met anyone who'd seen the shorts as a youngster and didn't like them; most people, even if they hadn't thought of the series in decades, could at least respond to "Conjunction Junction" with "What's your function?"

One of my favorites in the series is "Rufus Xavier Sarsaparilla," which is a cheerfully over-the-top explanation of the usefulness of pronouns, but if I had to pick a second it would probably be "The Tale of Mr. Morton." "Mr. Norton" is a story of predicates and loneliness which toys with melancholy and then resolves itself quite nicely with both humor and a bit of forward-thinking action. In terms of Gardner's theory, this episode is probably the most complete--it touches on all of them, really--but it's not as fun as "Rufus Xavier Sarsaparilla" or "Electricity, Electricity."

The program had a lot of good tracks, though, in addition to the ones mentioned already: "Three Is a Magic Number" is a tuneful work sampled by De La Soul; "Ready or Not, Here I Come" is about counting and multiplying by fives, with the trademark Schoolhouse Rock humor ("Look at that boy with seventeen fingers sticking up. How do you do that, kid?"); "Little Twelvetoes" is a sci-fi track about what it would be like if man had twelve fingers and toes (he'd count by the base-twelve system); "Sufferin' Till Suffrage" is a soulful song about Susan B. Anthony and other suffragettes; "Them Not-So-Dry Bones" explains bones and the need for calcium; and "A Victim of Gravity" is a comedic doo-wop science lesson.

The series is mostly very sensible, but a couple of the episodes made in the 1990s show the ad-men roots, with a blatant emphasis on consumption not apparent in the earlier ones. Which is not to say that the others are completely without problems; "Elbow Room" in particular indulges in the great national lie of Manifest Destiny, apparently agreeing that it was "our" destiny to expand across the country and implying, by extension, both that "we" are not black or Native American, and, further, that the black and Native American destiny was to be subjugated. It's ugly, vicious stuff packed in a saccharine melody, completely out of step with most of the series.

Also troubling is that suffrage got mention in the original series but slavery and civil rights both did not. In a series that spent three songs on the fight for independence, one on The Preamble, and another on the three branches of government, it's a bit jarring to jump ahead from that to Women's Suffrage. The series debuted in 1973, so it's possible that the producers or the network considered slavery and civil rights still (!) too contentious, especially for the Southeastern market, where much of the public has no compunctions about showing its racism. The series released new episodes in the 1990s, including ones dealing with computers and "The Tale of Mr. Morton," mentioned above. You'd think that would give the authors a chance to redress their error, but they didn't; I think the absence points towards one of those "polite fictions" the powerful like to indulge in to avoid dealing with uncomfortable discussions.

If self-perception and willful self-delusion are subtext in Schoolhouse Rock, they serve as the text itself in the experimental film Panorama Ephemera. The film starts with Don and Claire, a young man and woman sitting at a desk, being asked if they know what the signal was that will cause them to fall into a deep sleep again. Neither of them can remember it. The voice offscreen says that perhaps they can find the signal.

The film cuts to a clip asking if we think it's strange that the land might develop a fondness for its people; and both the film's means and its main theme are soon apparent. Edited together from what Rick Prelinger calls "ephemeral films," Panorama Ephemera incorporates social guidance films, industrial films, home movies, and other disparate sources into a feature-length examination of how the U.S. portrays itself.

The clips are often grouped thematically and, in a sense, the film is a glorification of B-roll--these kinds of clips are often used to depict some point being made in documentaries--but in another sense the film is a glorification of the invisible, a cousin to Joseph Cornell's Rose Hobart, which Girish wrote about as decontextualizing reaction shots to foreground them in the viewer's attention.

In Panorama Ephemera the connections between the clips are sometimes blatant and sometimes not--footage of a scientific experiment using mice follows footage of toy cars on a toy highway, weaving past each other. In the experiment, mice must push a button for rewards; one of the mice ends up doing all the work and the other two become social parasites. A title card in the original footage informs us "A 'class society' has emerged." It's tempting to relate this experiment to the previous shot of cars and to dismiss the traffic as part a "rat race"; it's equally tempting to relate the experiment to later footage of police beating down union members on strike.

Many of the connections, though, are less immediately obvious. Halfway through the film, Don and Claire witness the signal again: a book closes. They both fall into hypnosis. The offscreen voice continues asking them questions. In the clips that follow, a principal arrives at school to serve as poll-place volunteer; settlers travel west; a worker loads corncribs with corn; a couple drives through the country to picnic, the woman working herself up to announce that she's pregnant, the man steadfastly not understanding her allusions.

There is so much to consider, so much of it open to interpretation and so much of it potentially related to half a dozen other clips both before and after, that interpretation is something of a challenge. It's clear, though, that the film deals with some overarching themes, conveyed directly through visuals and through diegetic sound: dependence on oil, mechanization, alienation, anxiety about child safety, consumption as an entertainment or distraction.

What isn't clear, even as Don and Claire come out of their long hypnosis, is whether we the audience are waking up as well. A woman sitting in a circle of friends states that sometimes the land loves its people and that sometimes people must be hurt to force them to learn. In the next clip a cat sitting on a windowsill gets up and goes to clean another cat's head. The footage could point towards selfless socialization, an answer to the alienation presented earlier; or it could be an echo of the class societies that the mice established and the police enforced. It's possible the film, like The Day the Earth Stood Still, was meant to end with a lingering question rather than an easy statement.

Sing along with "Rufus Xavier Sarsaparilla."

[Schoolhouse Rock! @ amazon.com]

[Panorama Ephemera @ archive.org]

Don and Claire and Rufus Xavier Sarsaparilla

Schoolhouse Rock! -- Rufus Xavier Sarsaparilla

If you're in your 40s or younger and grew up in the U.S. you're probably familiar with Schoolhouse Rock. A series of educational musical cartoon shorts, three minutes apiece, the episodes aired between Saturday morning cartoons from 1973 through to the mid-1980s. The shorts took on a number of subjects, falling into broad areas like math, English, science, civics and history; but they were not dryly "educational"; instead, they were infectious entertaining mnemonics apt to get you singing along, even about multiplication tables or interjections.

In this regard, the shorts were ahead of their time, integrating perfectly with Howard Gardner's theory of Multiple Intelligences, which holds that there aren't simply two kinds of intelligence (linguistic/verbal and logical/mathematical) but at least eight, including visual/spatial, bodily/kinesthetic, musical, naturalist, intrapersonal, and interpersonal. I've never met anyone who'd seen the shorts as a youngster and didn't like them; most people, even if they hadn't thought of the series in decades, could at least respond to "Conjunction Junction" with "What's your function?"

One of my favorites in the series is "Rufus Xavier Sarsaparilla," which is a cheerfully over-the-top explanation of the usefulness of pronouns, but if I had to pick a second it would probably be "The Tale of Mr. Morton." "Mr. Norton" is a story of predicates and loneliness which toys with melancholy and then resolves itself quite nicely with both humor and a bit of forward-thinking action. In terms of Gardner's theory, this episode is probably the most complete--it touches on all of them, really--but it's not as fun as "Rufus Xavier Sarsaparilla" or "Electricity, Electricity."

The program had a lot of good tracks, though, in addition to the ones mentioned already: "Three Is a Magic Number" is a tuneful work sampled by De La Soul; "Ready or Not, Here I Come" is about counting and multiplying by fives, with the trademark Schoolhouse Rock humor ("Look at that boy with seventeen fingers sticking up. How do you do that, kid?"); "Little Twelvetoes" is a sci-fi track about what it would be like if man had twelve fingers and toes (he'd count by the base-twelve system); "Sufferin' Till Suffrage" is a soulful song about Susan B. Anthony and other suffragettes; "Them Not-So-Dry Bones" explains bones and the need for calcium; and "A Victim of Gravity" is a comedic doo-wop science lesson.

The series is mostly very sensible, but a couple of the episodes made in the 1990s show the ad-men roots, with a blatant emphasis on consumption not apparent in the earlier ones. Which is not to say that the others are completely without problems; "Elbow Room" in particular indulges in the great national lie of Manifest Destiny, apparently agreeing that it was "our" destiny to expand across the country and implying, by extension, both that "we" are not black or Native American, and, further, that the black and Native American destiny was to be subjugated. It's ugly, vicious stuff packed in a saccharine melody, completely out of step with most of the series.

Also troubling is that suffrage got mention in the original series but slavery and civil rights both did not. In a series that spent three songs on the fight for independence, one on The Preamble, and another on the three branches of government, it's a bit jarring to jump ahead from that to Women's Suffrage. The series debuted in 1973, so it's possible that the producers or the network considered slavery and civil rights still (!) too contentious, especially for the Southeastern market, where much of the public has no compunctions about showing its racism. The series released new episodes in the 1990s, including ones dealing with computers and "The Tale of Mr. Morton," mentioned above. You'd think that would give the authors a chance to redress their error, but they didn't; I think the absence points towards one of those "polite fictions" the powerful like to indulge in to avoid dealing with uncomfortable discussions.

If self-perception and willful self-delusion are subtext in Schoolhouse Rock, they serve as the text itself in the experimental film Panorama Ephemera. The film starts with Don and Claire, a young man and woman sitting at a desk, being asked if they know what the signal was that will cause them to fall into a deep sleep again. Neither of them can remember it. The voice offscreen says that perhaps they can find the signal.

The film cuts to a clip asking if we think it's strange that the land might develop a fondness for its people; and both the film's means and its main theme are soon apparent. Edited together from what Rick Prelinger calls "ephemeral films," Panorama Ephemera incorporates social guidance films, industrial films, home movies, and other disparate sources into a feature-length examination of how the U.S. portrays itself.

The clips are often grouped thematically and, in a sense, the film is a glorification of B-roll--these kinds of clips are often used to depict some point being made in documentaries--but in another sense the film is a glorification of the invisible, a cousin to Joseph Cornell's Rose Hobart, which Girish wrote about as decontextualizing reaction shots to foreground them in the viewer's attention.

In Panorama Ephemera the connections between the clips are sometimes blatant and sometimes not--footage of a scientific experiment using mice follows footage of toy cars on a toy highway, weaving past each other. In the experiment, mice must push a button for rewards; one of the mice ends up doing all the work and the other two become social parasites. A title card in the original footage informs us "A 'class society' has emerged." It's tempting to relate this experiment to the previous shot of cars and to dismiss the traffic as part a "rat race"; it's equally tempting to relate the experiment to later footage of police beating down union members on strike.

Many of the connections, though, are less immediately obvious. Halfway through the film, Don and Claire witness the signal again: a book closes. They both fall into hypnosis. The offscreen voice continues asking them questions. In the clips that follow, a principal arrives at school to serve as poll-place volunteer; settlers travel west; a worker loads corncribs with corn; a couple drives through the country to picnic, the woman working herself up to announce that she's pregnant, the man steadfastly not understanding her allusions.

There is so much to consider, so much of it open to interpretation and so much of it potentially related to half a dozen other clips both before and after, that interpretation is something of a challenge. It's clear, though, that the film deals with some overarching themes, conveyed directly through visuals and through diegetic sound: dependence on oil, mechanization, alienation, anxiety about child safety, consumption as an entertainment or distraction.

What isn't clear, even as Don and Claire come out of their long hypnosis, is whether we the audience are waking up as well. A woman sitting in a circle of friends states that sometimes the land loves its people and that sometimes people must be hurt to force them to learn. In the next clip a cat sitting on a windowsill gets up and goes to clean another cat's head. The footage could point towards selfless socialization, an answer to the alienation presented earlier; or it could be an echo of the class societies that the mice established and the police enforced. It's possible the film, like The Day the Earth Stood Still, was meant to end with a lingering question rather than an easy statement.

Sing along with "Rufus Xavier Sarsaparilla."

[Schoolhouse Rock! @ amazon.com]

[Panorama Ephemera @ archive.org]

Comments:

<< Home

This is great, Tuwa. A wild recontextualization of Schoolhouse Rocks! Does your post participate in that avant garde blogathon?

Thanks, Amy. And that's a good question; I was wondering the same thing. It's about four days late for the avant-garde blogathon, and only the last half is about experimental film, so I don't know....

There's some good reading in that blogathon which I'm still wading through. Impressive work.

¶ Post a Comment

There's some good reading in that blogathon which I'm still wading through. Impressive work.

<< Home